You are where I am not, and I am where you are not

Artistic manifestations in experiencing the absence of another

Ilana Reynolds & Sabrina Huth

Journal für Psychologie, 30(2), 111–127

https://doi.org/10.30820/0942-2285-2022-2-111 CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 www.journal-fuer-psychologie.deSummary

This article reflects a four-year artistic research process between us, choreographers Sabrina Huth and Ilana Reynolds. In the frame of our artistic research project Imagined Choreographies we circulate around questions of how to encounter a body that is physically absent. What are the conditions and modalities of such a being-with? And what might be its implications for the way we build and shape relationships nowadays? By presenting three different artistic manifestations in the field of dance and choreography, the article articulates the creative strategies and artistic research methods we have developed to address these questions; such as alternative space-time structures and material traces as intermediaries to the absent other. The methodology behind our research strongly focuses on the »act« within our practice, the embodied knowledge produced from those actions, and the documentation of those actions. For example: setting up shared performance events without coming together at the same time and place, developing extensive written reflections/observations and documentation towards the working process and performative setups. As artistic practitioners positioning ourselves in dance and choreography, our research aims to build creative potential for the mind and body to explore layers of imagination, the fiction of another person, and potentially new forms of togetherness. Through this work, we believe to offer new perspectives on discourses around »bodily closeness« within not only the artistic realm but also the social sciences.

Keywords: Artistic research, dance/choreography & performance, presence of absence, absent body, alternative space-time structures, togetherness at a distance

Zusammenfassung

Du bist, wo ich nicht bin, und ich bin, wo du nicht bist

Künstlerische Manifestationen im Erleben der Abwesenheit eines anderen

Dieser Artikel reflektiert einen vierjährigen künstlerischen Forschungsprozess zwischen uns, den Choreografinnen Sabrina Huth und Ilana Reynolds. Im Rahmen unseres Projekts Imagined Choreographies kreisen wir um die Frage, wie man einem physisch abwesenden Körper begegnen kann. Was sind die Bedingungen und Modalitäten eines solchen Miteinander-Seins? Und welche Auswirkungen könnte es auf die Art und Weise haben, wie wir heutzutage Beziehungen gestalten? Am Beispiel von drei verschiedenen künstlerischen Manifestationen im Bereich Tanz und Choreografie stellt der Artikel die kreativen Strategien und künstlerischen Forschungsmethoden vor, die wir entwickelt haben, um uns den Fragen anzunähern, wie die Inszenierung alternativer Raum-Zeit-Gefüge und das Erweitern physischer Präsenz über verschiedene Medien und Platzhalter. Unsere Forschungsmethodik konzentriert sich dabei auf das verkörperte Wissen, das aus den Handlungen unserer künstlerischen Praxis hervorgeht, und die Dokumentation dieser Handlungen. Wir haben eine Reihe von Performance-Events inszeniert, ohne je zur gleichen Zeit und am gleichen Ort zusammenzukommen, und ausführliche schriftliche Reflexionen/Beobachtungen angefertigt, die den Arbeitsprozess und die performativen Arrangements begleiten. Unsere künstlerische Forschung im Bereich des zeitgenössischen Tanzes und der Choreografie zielt auf das kreative Potenzial körperlicher Abwesenheit und auf die Frage, wie dies die Imagination und die Fiktion des*der abwesenden Anderen stimulieren und potenziell neue Formen des Miteinanders erzeugen kann. Wir glauben, dass wir mit dieser Arbeit neue Perspektiven auf Diskurse über »körperliche Nähe« nicht nur im künstlerischen Bereich, sondern auch in den Sozialwissenschaften eröffnen können.

Schlüsselwörter: Künstlerische Forschung, Tanz/Choreografie & Performance, alternative Raum-Zeit-Gebilde, physische An-/Abwesenheit, Miteinander-Sein auf Distanz

1 Introduction

We (Sabrina Huth and Ilana Reynolds) have both worked in the fields of choreography, contemporary dance, and dance education for the past ten years and received our Master’s Degrees separately in Contemporary Dance Education and Artistic Research. Our joint choreographic work is anchored in the broad, sometimes nebulous field of artistic research. According to Kathrin Busch (2009), artistic research can range »from the simple integration of philosophical or scientific knowledge to the establishment of artistic research as a form of institutionalized self–examination and scientification of artistic practice« (2). Henk Slager (2009) even stages the academic discipline of artistic research as a »nameless science«; an »as-yet undefined sanctuary for creative experiment and knowledge production« (ibid., 1). In practical terms, this mystified non-definition or all-definition is not very useful, which leads us to the question: which approaches to artistic research do we refer to?

We approach the field of artistic research as a framework to analyze the phenomenon within the »act« of creating choreographic work, one primarily experienced through the body and grounded in the material world. By literally standing with both feet on the ground and connecting to gravity, the embodied experience of being in time and space marks a point of reference; it builds the foundation of »our perception, our understanding, and our relationship to the world and other people« (Borgdorff 2012, 124). Henk Borgdorff calls this the »realism of Artistic Research« (ibid.). Instead of observing phenomena from a hovering and distant perspective, artistic research as an academic discipline analyzes phenomena in and through the act of participating; it grounds itself in the material world. To Borgdorff it is defined as material thinking in and through artistic practices and creations. Furthermore, thoughts arising from reflections on artistic research as an academic discipline resonate with performance theorist and choreographer Bojana Cvejic’s (2013) conceptual framework of posing problems as a choreographic strategy. Referring to the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze she illuminates the capacity of choreography to express thoughts in terms of the production of problems as objects of ideas. According to Cvejic, the invention of a problem isn’t about uncovering an already existing question; neither is it a rhetorical question that cannot be answered. To produce a choreographic problem rather implies »constructing terms, in which it will be stated, and conditions it will be solved in« (ibid., 46). Moreover, it entails the »probing of a path in which new compositions of movement and body are differentiated« (ibid., 49). In our case, by posing the question of how to encounter an absent body, we develop new choreographic strategies and forms of embodied knowledge. We explore what forms of artistic practice/creation and strategies are developed around the simple fact that one is always absent from the other and vice versa. As a result, we encounter ways to »meet« and exchange within those conditions.

The source of our research and questions about absent bodies emerged from the sheer fact that we were meant to work together in Vienna for a joint week-long residency called Mind the Dance during the 6th IDOCDE (International Documentation of Contemporary Dance Education) Symposium at the Impulstanz Festival in Vienna, Austria in July 2018. Ilana never made it to Vienna, nonetheless, we decided to collaborate. In resonance with the symposium’s focus on collectivity, collaboration, and immediacy, we wondered how else might we come together, and what else, together, we might do: how were we going to collaborate within a dance/choreographic context without sharing the same time-space? These questions and the condition of physical absence evolved into a continuously unfolding project where togetherness, agency, creative output, and trust became founding pillars in our artistic research Imagined Choreographies – an overarching choreographic approach, where the basis of the research is how to encounter a body that is absent. To this day, we have never physically met.

In a time where the measure of presence is no longer closeness, where should my body be? In a time where the measure of closeness is not touch, how do we meet? (Huth 2019)

During public presentations, audience members, colleagues, and friends approached us to share their own stories of absence: the absence of a lover in a romantic long-distance relationship, the absence of a family member imposed by political circumstances, flight and migration, the absence of a physical counterpart in virtual reality environments or video conference meetings, the absence of a collaborator due to working conditions demanding ever more flexibility, adaptability and responsiveness. Staging the presence of someone who is, in fact, absent touches upon a broader social and cultural phenomenon: the dismantling of spatial proximity and the feeling of closeness. In our globalized age, entanglements reach way beyond what one might even perceive: »Every act results from more than one can know, and bears consequences upon more than one knows,« dancer and choreographer Alice Chauchat (2017, 30) points out. Fostered by continually evolving communication and information technologies, the usage of mobile devices, and the impact of social media networks, like Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, Twitter, etc., we have moved towards becoming involved with the world as a whole; lessening the geographically defined gap between one another. In The Medium is the Maker J. Hillis Miller (2009) states that modern telecommunication media »have made more or less instantaneous touching-, feeling-, knowing-, seeing-, hearing-at-a-distance the most everyday experience imaginable«. (ibid., 2) At the same time, whilst transforming from local to global beings, we might have widened the gap with what is physically close to us. The very tissue of our spatial and relational experience has altered. Anthony Giddens (1990) recognized thirty years ago, »conjoining proximity and distance in ways that have few close parallels in prior ages« (ibid., 140). Today, not only but even more since the global pandemic and in its aftermath, social isolation and digitally mediated forms of togetherness co-exist in a bewildering temporality and spatiality. We live in a »contorted form of togetherness« as Kris Cohen (2017, 5) phrases in his book Never Alone, Except for Now. We live in a time, in which the measure of presence is not closeness, and the measure of closeness is no longer touch.

Since early 2020, the world has been shaken by a global pandemic. Though the project didn’t emerge from this event, it touches, nonetheless, upon topics that have become relevant for many of us in one way or another. Our concepts of space, time and the relationships we live in have fundamentally changed. In such a situation how we relate to our sense of touch and our desire to be physically close changes as does the kind of relationship with ourselves, others and the world around us. In our wildest dreams, we could not have imagined that the situation we put ourselves in, out of a conscious artistic decision for mutual absence, would become a reality for people all over the world. Due to social distancing and precautionary measures, in some way, the experimental setups we created have become a sort of bewildering truth.

Up until now, our artistic research has manifested in a series of shared performance events presented in Germany and across Europe including the performance installation You are here (2019), the live performance Dance with me (2019), and the latest live performance A meeting that never took place (2021). As dancers and dance makers exploring one another’s absence – and the presence of this absence – the article aims to conceptualize, articulate, discuss and materialize ways of coming physically closer to another one through embodiment, perception and the act of performance-making. It gives access to the choreographic thinking and reflection within and around these multifaceted manifestations of our artistic collaboration by producing a communicative platform that weaves together the documentation, writings and artistic works.

2 On absence, presence and the presence of absence

During our four-year collaboration, negotiations between micro and macro scales of expressions – between what is happening inside the dance studio and the world outside – became a constant companion during the research-creation process. Through performance installations, performances and publications, we intended to uncover ways of further investigating the relationship between the absence and presence of another person. The terms »absence« and »presence« refer to fundamental states of being; may it be »the state or condition of not being present« or »the state or condition of being present« (Bell, 2019). This is why, with philosopher Amanda Bell (2019), it is hard to define absence and presence without referencing themselves. The difficulty, as she concludes, stems from the fact that both terms depend on the notion of being; and the »primary definition of being as to have or occupy a place … somewhere … Expressing the most general relation of a thing to its place« (ibid.) In accordance, etymologically the term absence derives from Latin absentia, present participle of ab-esse ›to be away from‹; and the term presence from Latin preasentem, present participle of præ-esse ›be before, be at hand‹. Consisting of the verb esse ›to be‹ and the respective prefix ab ›off, away from‹ or prae ›before‹, both terms indicate the relation between the quality or state of having an existence and the condition of doing so. Consequently, »being is not inexplicable or transcendent, but exists within a framework or state« (Bell 2019). The definitions of presence and absence explicitly rely upon the states within which they are found: the world, images and representations – to name a few examples. The state within which the notions of absence and presence are developed in this research are mainly set up within a strict space/time construct: We never share the same space and time simultaneously, but rather share the same space at different times or share the same time in different spaces. These constructs alone created a new set of actions and strategies to experience the others’ absence or in some cases the absent presence of the other.

In line with the philosopher Alva Noë, we approach ›absence‹ not so much as a state of »being away« or »being off« but rather as a different kind of presence. In Varieties of Presence, Noë (2012) thoroughly elaborates on a whole range of possible presences, including the one which withdraws or has withdrawn: the presence in absence. In contrast to the traditional representational theory of mind and its companion internalism which makes perception a somehow internal affair and »the world as devoured by the mental« (Finke 2013, 214), Noë (2012) articulates an account of perception and perceptual consciousness due to which presence is enacted rather than merely found: »Perception is not something that happens to us, or in us, (…), it is something we do« (Noë 2004, 1). His main thesis is that all kinds of presences result from our efforts of achieving access to the world: »Presence is achieved, and (…) its varieties correspond to the variety of ways we skillfully achieve access to the world« (Noë 2012, xi). Presence results from how we involve our practical skills and knowledge in making persons and things available to ourselves.

Noë’s way of turning presence in absence into a »yet undetermined hiddenness« (Finke 2013, 215) – but fully acknowledged as a kind of presence – is what characterizes the enactive approach. It resonates with how we have been experiencing one another’s absence as some kind of presence in absence. We both live in faraway places; too far away to immediately see, hear, touch or smell the other. Along with Noë’s (2012) claim that »we achieve access to the world around us through skillful engagement,« (ibid., 2) our respective presence is grounded on the skills and knowledge we have to make contact with another. Our artistic collaboration is built on the constraint that we never physically meet. Yet, we have access to each other in the sense of being available and present. What defines our experience of one another’s presence in absence is not merely a matter of (spatial) proximity, of being more or less distant from each other; it is a matter of availability. We become present to each other within specific time/space frameworks where we either inhabit the same space at different times or the same time at different spaces; so-called spaces of access – to introduce another main concept of Noë (2012, 33–35). Each access-space and performative set-up consists of different structures »determined by the repertoires of skill that structure them« (ibid., 34). and creates a set of conditions to experiment with modes of being together whilst being physically remote. Each time a shared performance event, a ›never meeting‹, comes into being, »it does so ›just this way‹, in direct accordance with how the constraint enables this singular set of conditions« (Manning 2016, 90).

3 Strategies and methods of connecting to the absent other illustrated through three artistic manifestations

3.1 You are here (2019): Anarchival traces of the absent other while being in the space at different times

Ilana Reynolds performing in the show window. Performance installation You are here, 2019. Photos: Ester Eva Damen

Sabrina Huth performing in the show window. Performance installation You are here, 2019. Photo: Ester Eva Damen

Our first artistic manifestation was a five-day durational performance installation called You are here, where we inhabited the same exhibition space at different times. Books, drawings, paper string and empty coffee cups accumulated in the space and created an installation of traces left behind for the other to engage with and alter. Gradually, the exhibition space, a show window in the Amsterdam De Pijp neighborhood, became a collage of composed books, letters, notes, stories, and small dances. These repertories of traces, as we called them, became the connecting mediators between each other and the audience passing by in which we experienced, connected to and composed the other’s absence. Inspired by The Go-to How to Book of Anarchiving (Murphie ed. 2016), anarchiving was used as a framework to create the process-oriented performance space of You are here. Rather than documenting the content of the event, anarchival processes capture traces of the event’s liveness, which might set the stage for the next event to occur. In this sense, with Brian Massumi (2016), the anarchive always needs an archive »from which to depart and through which to pass« (ibid., 7). Unlike an archive concerned with preservation and coding practices, the anarchive aims at stimulating new modes of production. It is an excess energy of the archive: »a kind of supplement or surplus-value of the archive, (…) a feed-forward mechanism for lines of creative process, under continuing variation« (ibid.).

In the case of You are here, the materials and objects we brought to the exhibition space at the beginning of the event, such as the printed emails we wrote to each other, or the book that we both read during the previous collective reading sessions1served as an archive to depart from; in Massumi’s words: they became »compositional forces seeking a new taking-from« (ibid). Being constantly placed, displaced, replaced, etc. they inspired something different from their form or defined purpose. As a result, another kind of trace emerged from them. In this way, what was left behind served as a potential for something else to come. The traces became an anarchive of experiences and connecting intermediaries that could not be fully possessed due to their ephemerality but were impulses to push the research further. In this sense, Murphie (2016) defines traces as the tip of the iceberg that allude to the submerged sensuous, affective and discursive experiences which created them. As we (Ilana and Sabrina) would say:

»A trace is multiple.

A trace is a formless memory (of an event).

A trace is a mediator in the proof of our existence for another.

A trace is a container, a snapshot, or leftover coffee drips on the edge of a paper cup. A trace limits the past’s unlimited potential to unfold in the future.

A trace holds content of a different nature.

Our lives are composed of traces, outlines, pathways, images, sketches, memories, and narratives.

Everything is a trace of something else. Not all traces are meant to last forever« (Huth and Reynolds 2020, 41).

Moreover, according to Massumi (2016), the anarchive is in its nature a »cross-platform phenomenon« (ibid., 7). Respectively, You are here manifested in, through and in-between different media: written and spoken word, objects, materials and the physicality of the bodies inhabiting the exhibition space. In an anarchival sense, the performance installation was activated in the relays »between verbal and material expressions, (…), and most of all between the various archival forms it may take and the live, collaborative interactions that reactivate the anarchival traces, and in turn create new ones« (ibid). In Ilana’s words: »[The] work needs all mediums. It can’t just exist in one form. All mediums are helping the thing itself to be the thing itself, the choreography.« By the end, we had found ways to connect to one another through the space we shared and the objects and material left behind, but what remained as a question in our minds was the body. How do we connect kinesthetically, to the very skin and aliveness of our bodies?

3.2 Dance with me (2019): Kinesthetic empathy, fiction and imagination while being in different spaces at the same time

Ilana Reynolds on stage and Sabrina Huth on-screen performing Dance with me. Modes of Capture Symposium, Ireland, 2019. Photo: Liz Roche Dance Company

Sabrina Huth on stage and Ilana Reynolds on-screen performing Dance with me. Unfinished Fridays, Lake Studios Berlin, 2019. Photo: Lake Studios Berlin

»It was as if they were in the nervous system of the other« (Roche 2019). Digging into the question of how to kinesthetically encounter, connect and empathize with an absent body for the Dance with me 2 duet we flipped the time/space paradigm into sharing the same moment(s) in time but in different spaces. Hereby, we touched on another level of connection, one not linked to a physical object and material traces but rather to the very aliveness of our moving bodies. With Erin Manning (2007), the skin that touches and is touched is our first and foremost sense organ through which we encounter the world we are embedded in. Through touch we reach out to what or whom we do not yet know; we reach out to become engaged »in a reciprocal engagement with the unknowable« (ibid., 49). At the same time, through touch we embody difference; it ascertains the differentiation of where my body begins and your body ends. Given the vital importance of touch for human relationships, in the duet Dance with me we posed the speculative question of how to reach out, to ›touch‹ one another without ever touching one’s skin. Can we expand our perceptual attention towards the untouchable; towards the immanent, hidden or latent channel of communication? And how would such a »telepathic touch« affect the body moving in space/time?

Inspired by a movement practice developed by the choreographer Alice Chauchat called telepathic dancing3, the basic principle of the Dance with me duet was to imagine being in the space of the other and/or imagining that the other was in your space. Without speaking but keeping the same time frame we sent dances to the other who then received them by dancing them. The roles then reversed. We practiced this for at least a month which developed the following structure for the duet: one dancer is projected live within the space of the other dancer, who is performing in front of an audience. Both dancers follow the same movement score and design the same physical space by using tape as a way to mark the virtual space of the projected dancer. To stimulate the relational and sensorial imagination between us, we invited in, what Chauchat (2017) calls generative fiction. By imposing imagined and speculated parameters to the movement performed on stage, we set conditions to project ourselves into the other’s space and vice versa; to host the absent other in one’s sensorimotor activity. In this way, the imagination of sending and receiving dances to and from each other was used not to show that one is pretending, »or to display the fakeness in a revelatory gesture« (Chauchat 2017, 35). Instead, the proposition of a telepathic touch mediated through the dances we shared, whether fictional or actual, transformed the capacity to move in relation to one another. And if one pretends well enough, Chauchat concludes, even »to the point of convincing oneself that one experiences the fiction« (ibid.), one is efficiently transformed.

Accordingly, and in line with the phenomenological emphasis on the body’s belongingness to the world, ›telepathy‹ is approached as a state of being for the other. Professor of philosophy and dance at Mälmo University Susan Kozel (2007) states: »To feel one’s body is also to feel its openness to the other: the other’s capacity to receive sensory information from me is implicated in my sensoriality. It is as if communication flow to and from others is hardwired into my very structure; I moderate and regulate, decipher and interpret, inhale and exhale, sensing my own and other’s bodies at all times« (281). Following Merleau-Ponty’s (1969) unfinished work The Visible and the Invisible, telepathic connection is not limited to the popularized version of a latent message conveyed between two beings by psychic means; but simply that »the other’s sensoriality is implicated in my own« (244–245). As if encountering the other becomes a form of »having-the-other-in-one’s-skin,« (ibid., 283); or as if »to feel one’s body is also to feel its aspect for the other,« (Merleau-Ponty 1969, 244–45).

Addressing telepathy from the phenomenological point of view allows us to foreground its sensorial and perceptual aspects; and in particular, the kinesthetic dimension of relating to someone not being here. What is more, it links to another key concept regarding social interaction and communication: kinesthetic empathy. In terms of definition, on one side, in a broad sense »kinesthesia«4 can be understood in relation to the sensation of movement and position. It is informed by senses such as hearing and vision, as well as internal sensations of body position and muscle tension (Reynolds 2007, 185). Embedded in a network of sensory modalities, including touch and hearing, kinesthesia is »constituted across sense modalities,« (Gallagher and Zahavi 2008, 95) meaning that an action or a movement can be experienced, for instance, both as a visual image and as a movement sensation. On the other hand, the term »empathy«, in German »Einfühlung«, was coined in its modern sense of »feeling into something« by Robert Vischer in 1873 as part of his doctoral thesis on aesthetics and was later promoted by Theodor Lipps. Both in Vischer’s and Lipps’ writings kinesthetic sensation was considered an intrinsic part of empathy (Rova 2017, 165). In its strongest form, as Reynolds (2012) states, »empathy involves embodied simulation and imagined substitution of one agent for another: for a fleeting moment, perhaps, I simulate your action, and in doing so I imagine that I occupy your place, that I am the vicarious agent of your movement, your experience, your utterance« (124). Bringing the two terms »kinesthesia« and »empathy« together again, in Dance with me, we put the focus on the kinesthetic dimension of »feeling into someone«; the sensation of being moved in an embodied rather than cognitive sense and the capacity to respond to the affective experience of another person.

3.3 A meeting that never took place (2021): Exploring time/space setups through the analog body

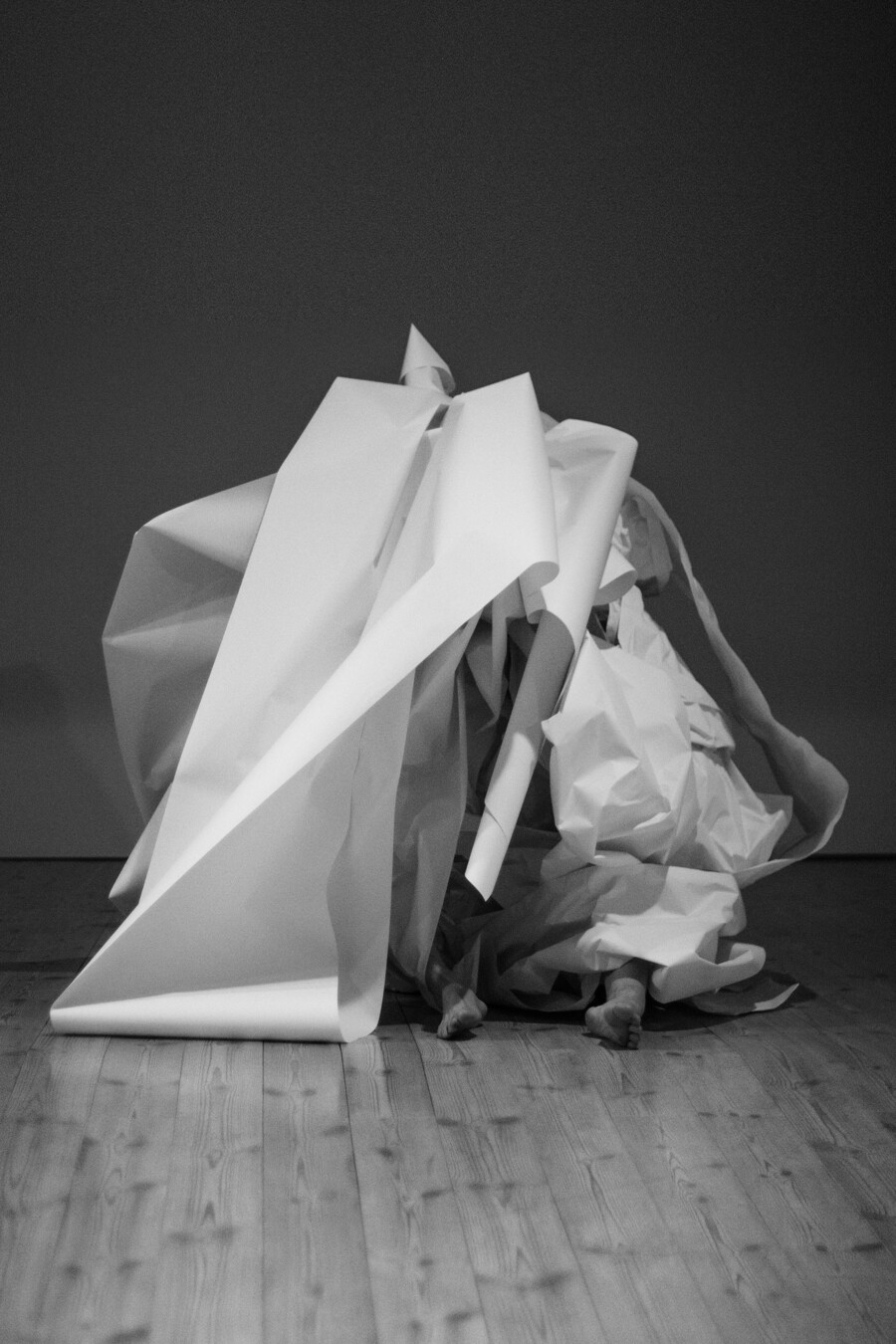

»Paper body« in A meeting that never took place, Lake Studios Berlin, 2021. Photos: thisismywork.online

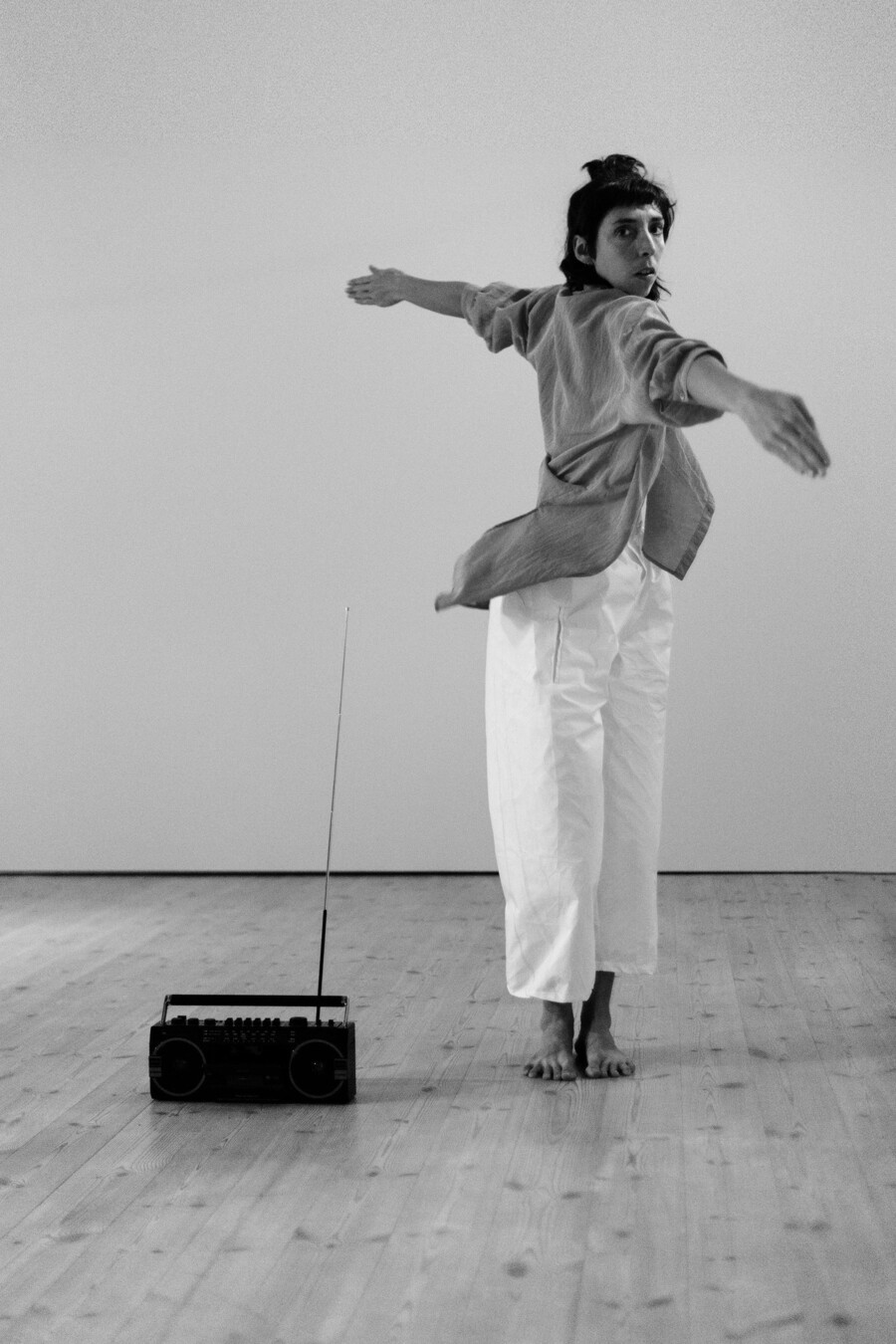

Sabrina Huth performing in A meeting that never took place, Lake Studios Berlin, 2021. Photos: thisismywork.online

»The absence of one has already become a part of the presence of the other. The refusal of a linear temporality is thematized and describes an intimate portrait of a relationship of two people, who know no nostalgia and are nevertheless determined by curiosity and longing for the other« (Hennermann 2021).

In the above quote, the dramaturg Célestine Hennermann (2021) aptly describes our latest performance A meeting that never took place which premiered in October 2021 at Lake Studios Berlin. The work weaves and embodies the story of our four-year-long collaboration of having never physically met. The performance unfolds as two narratives, simultaneously performed on two different stages in the same venue in front of a divided audience, and stages how through our ›never meeting‹ we have met time and time again. »The ›meeting‹ happens in the form of a line that has no beginning and no end; it continuously unfolds into new shapes and patterns. It is neither limited to space nor time« (Huth, letter #19, 19.08.2021).

The creation process of A meeting that never took place became a culmination of all the strategies outlined in the previous chapters and elaborated in the preceding four-year research period. What became apparent in the development of this work, however, was the use of analog practices as a fundamental and transformative artistic tool. Although we continue to communicate via digital technology our artistic practice predominantly manifests in the analog realm, for example in the form of handwritten letters, paper rolls, audio cassettes, recorded movement notations, shared movement scores, etc. Our focus on analog media was not out of a refusal of the digital or out of an »analog nostalgia« (Schrey 2014) but rather as a way to reveal factors such as originality, uniqueness, and imperfection that are attributed to analog media, such as coffee stains and scratched out words on a handwritten letter. Speaking of handwritten letters: During a three-month production period, each day we sent a letter to each other via mail reflecting on our rehearsal process which happened in different spaces. Sabrina was rehearsing in Berlin and Ilana in Magdeburg. The handwritten reflection letters included movement scores, drawings, cake recipes, and fictional stories of the other: what we imagined about the other, what we didn’t know, and what we did know through stories told to us by our collaborators. These letters carried the trace of the body and person who was no longer there but was nonetheless held, felt, heard and digested in the hands or ears of the body and person who carried them. The letters embodied the charm of the imperfect just as they allowed us to weave through time continuums of the present, past, and future:

»As I write this letter, I project into your future. As you read this letter, you sit in my past. Reading your notes, memories, or stories articulated your past through my present/future. Your thoughts expanded in reverberation with my body’s presence. They vibrated through my skin« (Huth and Reynolds 2020, 42).

On two separate stages, these handwritten letters transformed into 50-meter-long rolls of blank white paper folded, rolled, crumpled, and wrinkled into three-dimensional paper bodies: a skin to touch, be touched by and a body to dance with. Folded within the many layers of paper, we experimented with movement scores and detailed movement notations which we imagined to be in the body of the other. In one such score, called These are not my hands, we move, sense, feel and try to perceive that our hands are the others. These movement experimentations were framed within detailed movement notations such as: »I make a fist with my right hand, the left-hand cover’s the fist, hands come together, hands move apart and fall to the ground« (Reynolds, movement notation #1, 2021). The notations were sent through audio recordings and later, in combination with selected text from over 120 handwritten letters, recorded on cassette tapes and played through a ghetto blaster. Not only was the materiality and mobility of a fictional paper body present, but the ghetto blaster served as an emoting mediator of either one of our voices: an audio body expanding in space. In line with Massumi’s (2002) claim that »in sensation, the thinking-feeling body is operating as a transducer« (ibid., 135), we used analog material and practices to explore their potentially transformative force. »If the sensation is the analog processing by body-matter of ongoing transformative forces, then foremost among them are forces of appearing as such: of coming into being, registering as becoming« (ibid). In A meeting that never took place the materiality of the paper paired with the audio-cassette recordings recreated certain analog fragments of the absent other that were tangible, perceptible, and embodied by the other. They brought the absent and fictional body of the other into being. Moreover, the recreated fictional other paired with the physical presence of an actual moving body, the dancer becomes herself and the imagined other simultaneously. The dancer’s dancing becomes a duet between the actual and the fictional body on stage; it unfolds the missing link between the two dancers to reveal a meeting that takes place on the threshold between the tangible and the imaginable. Hereby, the dancer’s body always implies the presence of the other not being here and extends beyond what is immediately graspable or accessible to experience; neither what is totally outside of experience. By staging the presence of the other’s absence the dancer’s body manifests in what we call Imagined Choreographies; somewhere in between the dancers’ physical and fictional bodies on stage (even so not in the same time/space) and the fiction of an encounter with the absent other.

4 Feeding Forward

»As I wander in my steps, an image of you is by my side. With you, I come closer to sensing the multiplicity of time/events. These conditions create an experimental context to train trust, care, and solidarity; a way of being with and working together that exceeds boundaries of space and time and quantifiable measurements. Proximity and distance are playfully entangled, without seeking to close the gap between us« (Huth and Reynolds 2020, 43).

In the course of the collaborative project Imagined Choreographies and the artistic manifestations discussed in this article, we aim to encourage an alternative perspective on remote relationships; one that might include experiencing the presence in absence as a form of togetherness; a being-together-whilst-being-apart. We speculate on modalities of being with whilst being physically remote that move beyond getting nostalgic about the past and pessimistic about the future. Instead, we linger in the incongruity of modern relationships to see what else might emerge and how else we might relate to one another. In One World in Relation, the philosopher Édouard Glissant (2011) speaks in conversation with Manthia Diawara of the necessity to »consent not to be a single being« (ibid., 4–19). However, his phrase doesn’t claim hasty consensus, nor the reduction of other bodies to existing normative values, rules, actions and imagination. Instead, it encourages us to question what brings our individual bodies together and what tears them apart. The above quote describes the particular relationship we have been building while never meeting as one of disorientation rather than anything linear and, in that, a tremendous amount of closeness and intimacy has developed. Of course, nothing substitutes or surpasses the haptic presence of another being by your side. ›Never-meeting‹ can become a challenging and logistical entanglement that needs frequent revision and coordination. However, what we have discovered are the many ›other‹ ways to perceive one’s presence and that of another when the sharing of the same space/time paradigm becomes irrelevant. One must be open and trustworthy. The ability to perceive and receive beyond the boundaries of one’s skin allows one to enter new dimensions of togetherness and connection. In the pandemic’s aftermath and waning, the ability to connect to one’s own body and to that of another continues to be of utmost importance. In the same frame, the dances we make and the stories we tell or retell might need to take different shapes to discover more imaginary paths, explore absence as a presence, and a body in transformation.

In the future, and in an anarchival sense, the Imagined Choreographies project continues to feed itself forward. Rather than coming up with something new and, thereby, fulfilling capitalist expectations of productivity and self-exploitation, we aim to delve deeper and continue to unfold already existing artistic processes. In this way, the idea of the ever-new is countered by the idea of variation: like creating new versions of the same story and thereby developing new narratives, perspectives, and forms of artistic expression. Orbiting in a horizontal relational plane we ask ourselves: what new forms of absence and presence take place and where can new encounters manifest? And like any story, there are many ways to tell our story about a meeting that never took place.

Endnotes

- [1]

- From October 2019 to January 2020, once a week we conducted what we later called collective-reading sessions. In each of these sessions, at a certain time, in our respective places, we were reading and/or being with the same book in the imagination of the other doing so as well.

- [2]

- The duet Dance with me was presented during the Modes of Capture Symposium at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance and the University of Limerick which took place from June 21st-23rd 2019. The theme of the symposium was an exploration of the manifold means to capture creative processes and to engage with the threads, fragments, and layers that interweave throughout the process of dance-making.

- [3]

- The principle of Alice Chauchat’s telepathic dance is that the people watching the dance are sending the dance that is being danced by the dancer(s). This is a conceptual fiction, a proposal meant to stimulate a sensorial and relational imagination. Taking it as a fact, both dancers and watchers go through a process of (dis-)identification. The watchers appropriate the dance as an expression stemming from themselves, and the dancers disown the impulses that move them as belonging to someone else. Technically, the dancer's attention is very similar to the one practiced in Authentic Movement in terms of openness and spontaneity. The difference is conceptual, assigning impulses to exteriority rather than interiority. Telepathic dance considers movement as an alien expression that traverses the dancer and kinesthesia as a mode of perceiving otherness.

- [4]

- Kinesthesia is often named in relation to proprioception. With Reynolds and Reason (2012), »[s]ometimes kinesthesia and proprioception are used interchangeably, or one is subsumed into the other. For some, proprioception is defined as the sensing of one’s own position and movement stimuli from within the body, through sense receptors in the muscles, joints, tendons, and inner ear, as distinct from exteroception, the detection of environmental events through receptors in the eyes, ears, and skin« (ibid., 17). However, the distinction between inner/outer is not at all clear-cut and deeply interwoven.

References

Bell, Amanda. 2019. »absence/presence.« The Chicago School of Media Theory. Accessed September 3, 2019. https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/absence-presence/.

Borgdorff, Henk. 2012.The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. London: University Press.

Busch, Kathrin. 2009. »Artistic Research and the Poetics of Knowledge.« ART&RESEARCH: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts, and Methods. 2.2 (2009): 1–7. Accessed Dec. 12, 2017. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/busch.html.

Cohen, Kris. 2017. Never Alone, Except for Now. Art, Networks, Populations. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Cvejic, Bojana. 2013. »A Few Remarks about Research in Dance and Performance or – The Production of Problems«. In Dance [and] Theory, edited by Gabriele Brandstetter and Gabriele Klein, 45–50. Bielefeld: transcript.

Chauchat, Alice. 2017. »Generative Fictions, or How Dance May Teach Us Ethics«. In Post-Dance, edited by Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvardsen, and Marten Spangberg, 29–43. Stockholm: MDT.

Cohen, Kris. 2017. Never Alone, Except for Now. Art, Networks, Populations. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Diawara, Manthia. 2011. »One World in Relation: Édouard Glissant in Conversation with Manthia Diawara.« Nka 28: 4–19.

Finke, Stale. 2013. »Recovering Presence: On Alva Noë’s Varieties of Presence«. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology 44 (2): 213–222.

Gallagher, Shaun, and Dan Zahavi. 2008. The Phenomenological Mind: An Introduction to Philosophy of Mind and Cognitive Science. London: Routledge.

Gallese, Vittorio. 2008. »Empathy, Embodied Simulation, and the Brain: Commentary on Aragno and Zepf/Hartmann«. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 56: 769–781.

Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. United Kingdom: Polity Press.

Hennerman, Célestine (dramaturg, choreographer, and lecturer), unpublished program booklet to the piece »A meeting that never took place«, September 2021.

Huth, Sabrina, and Ilana Reynolds. 2020. »As I project into your future, you sit in my past«. Contact Quarterly 45 (1): 40–43.

Kozel, Susan. 2007. Closer. Performance, Technology, Phenomenology. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press.

Manning, Erin. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1969. The Visible and the Invisible. Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

Miller, J. Hillis. 2009. The Medium is the Maker: Browning, Freud, Derrida, and the New Telepathic Ecotechnologies. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

Murphie, Andrew, ed. 2016. The Go-to How to Book of Anarchiving. Montréal: The SenseLab.

Noë, Alva. 2004. Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Noë, Alva. 2012. Varieties of Presence. London: Harvard University Press.

Reynolds, Dee. 2012. »Kinesthetic Empathy and the Dance’s Body: From Emotion to Affect«. In Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices, edited by Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason, 120–135. Bristol: Intellect.

Reynolds, Dee. 2007. Rhythmic Subjects: Uses of Energy in the Dances of Mary Wigman, Martha Graham, and Merce Cunningham. Alton: Dance Books.

Roche, Jenny (senior lecturer at Irish World Academy Of Music & Dance), in discussion with the audience. June 2019.

Rova, Marina. 2017. »Embodying kinaesthetic empathy through interdisciplinary practice-based research.« The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55: 164–173.

Schrey, Dominik. 2014. »Analogue Nostalgia and the Aesthetics of Digital Remediation.« In Media and Nostalgia. Yearning for the Past, Present, and Future, edited by Katharina Niemeyer, 27–38. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan Memory Studies.

Slager, Henk. 2009. »Nameless Science. Introduction«. ART&RESEARCH: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts, and Methods, 2.2: 1–4. Accessed Dec. 5, 2017. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/slager.html.

Authors’ note

Ilana Reynolds and Sabrina Huth are freelance dance artists based in Göttingen and Berlin. Ilana completed her MA (2017) in Contemporary Dance Education at the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts. Sabrina completed her MA (2020) in Artistic Research at the University of the Arts Amsterdam and as a guest student at HZT Berlin. Under the condition of never physically meeting each other, they have developed the choreographic approach Imagined Choreographies to interrogate co-presence in physical absence. Since 2018, they have presented a series of performative events in Germany and across Europe. On stage, in galleries, and in written word they invite audience members into poetic landscapes in which the fiction and reality of the absent other are interwoven.