Auf dem Weg zu einem theoretischen Model von Spiritualität für die klinische Praxis: Eine amerikanische Perspektive

Zusammenfassung

Auf dem Weg zu einem theoretischen Model von Spiritualität für die klinische Praxis: Eine amerikanische Perspektive

Das Thema Spiritualität wurde in der Vergangenheit in weiten Teilen als völlig losgelöst von therapeutischen Konzepten gesehen. Doch scheint es, dass Patienten in der Psychotherapie in jüngster Zeit einen gestiegenen Wert auf Konzepte der Spiritiualität legen. Der folgende Beitrag soll ein theoretisches Modell vorstellen, dass PraktikerInnen im Umgang mit Spirituaität während der Therapie helfen kann. Innerhalb dieses Rahmens wird Spiritualität verstanden als die Suche nach dem Heiligen und setzt sich somit mit der Suche des Individuums nach dem Heiligen auseinander. Außerdem versucht das Model auch problematisierende Einflüsse auf das Verhältnis des Individuums zum Heiligen mit einzubeziehen und macht eine Unterscheidung zwischen gut und schlecht integrierten Formen der Spiritualität möglich. Schliesslich wollen wir anhand von klinischen Beispielen die erfolgreiche Integration von Spiritualität in die Therapie aufzeigen.

Schüsselwörter: Spiritualität, heilig, Psychotherapie, spiritueller Rahmen

Summary

Historically, the topic of spirituality has been largely disconnected from mental health treatment. However, recent evidence suggests that clients desire greater attention to spirituality in psychotherapy. The current paper provides a theoretical model for understanding and evaluating spirituality that can guide mental health treatment. This framework defines spirituality as a search for the sacred and addresses individuals' discovery of, attempts to conserve, and, at times, transform their views of the sacred. The model also considers the effects of stressors on an individual’s relationship with the sacred, and offers a way to distinguish well-integrated from poorly integrated forms of spirituality. We conclude with a review of successful attempts to address spirituality in mental health treatment.

Keywords: Spirituality, Sacred, Mental health treatment, Spiritual framework

Zusammenfassung

Auf dem Weg zu einem theoretischen Model von Spiritualität für die klinische Praxis: Eine amerikanische Perspektive Das Thema Spiritualität wurde in der Vergangenheit in weiten Teilen als völlig losgelöst von therapeutischen Konzepten gesehen. Doch scheint es, dass Patienten in der Psychotherapie in jüngster Zeit einen gestiegenen Wert auf Konzepte der Spiritiualität legen. Der folgende Beitrag soll ein theoretisches Modell vorstellen, dass PraktikerInnen im Umgang mit Spirituaität während der Therapie helfen kann. Innerhalb dieses Rahmens wird Spiritualität verstanden als die Suche nach dem Heiligen und setzt sich somit mit der Suche des Individuums nach dem Heiligen auseinander. Außerdem versucht das Model auch problematisierende Einflüsse auf das Verhältnis des Individuums zum Heiligen mit einzubeziehen und macht eine Unterscheidung zwischen gut und schlecht integrierten Formen der Spiritualität möglich. Schliesslich wollen wir anhand von klinischen Beispielen die erfolgreiche Integration von Spiritualität in die Therapie aufzeigen.

Schlagwörter: Spiritualität, heilig, Psychotherapie, spiritueller Rahmen

»Priests should stay out of therapy and therapists should stay out of spirituality« (Prest & Keller, 1993, p. 139). This quotation is a stark representation of one view of the relationship between spirituality and psychotherapy. This attitude has been prevalent historically and has led to a disconnection between spirituality and mental health treatment. Many mental health professionals are uncomfortable discussing spirituality in therapy. Some may experience irritation when clients raise spiritual issues. Some may dismiss the relevance of spiritual beliefs and, instead, attempt to find the »real truth« underlying the client’s experience. Others may want to be responsive to spiritual issues but feel uneasy and uncertain how to proceed. The end result is that mental health professionals generally neglect or overlook the spiritual dimension in mental health treatment.

Recipients of health care in the USA report dissatisfaction with the lack of spiritually-sensitive care. Forty-five percent of patients on an inpatient rehabilitation unit stated that too little attention was given to their spiritual and religious concerns and 73% indicated that no one on the staff spoke to them about spiritual issues (Post, Puchalski, & Larson, 2000). Individuals receiving mental health services report similar neglect of their spirituality in treatment. Two-thirds of a sample of adults with serious mental illness indicated that they would like to discuss spiritual issues in therapy but only half were doing so (Lindgren & Coursey, 1995). In a spiritual issues group for the seriously mentally ill, participants welcomed the opportunity to discuss their spirituality. As a group, they agreed that it was the first chance they had to discuss their spirituality in many years of mental health treatment (Phillips, Lakin, & Pargament, 2002). Explanations for the Lack of Integration

There are multiple explanations for the lack of integration of spirituality into mental health treatment. First, mental health practitioners differ significantly from their clients in their religious beliefs and practices. For example, 58% of a national U.S. sample reported that religion is very important to them while only 26% of clinical and counseling psychologists described religion as very important to them. Similarly, over 90% of the U.S. population reports belief in a personal God. However, only 24% of clinical and counseling psychologists endorse this belief (Shafranske, 2001). Therapists may underestimate the salience of spirituality in their clients' lives by projecting their own irreligiousness on to the clients they serve.

Second, practitioners may perceive a conflict between the worldviews and values of psychology and religion. For example, psychology and religion can be seen as offering opposing explanations for the meaning of events. While religion explains events such as natural disasters and experiences of good fortune through attribution to the sacred (e.g. »God moves in mysterious ways« and »no one can know the mind of God.«), psychology attributes events to human or natural forces.

Psychology and religion can also be perceived as differing in their views of control. As a field, clinical psychology focuses much of its attention on attempts to help individuals gain control over the previously uncontrollable (Pargament, 1997). For example, psychodynamic approaches to psychotherapy work to bring the unconscious into conscious awareness. Behavioral approaches help individuals master the contingencies controlling disruptive behaviors. Cognitive therapy teaches people to control their thoughts and feelings in order to improve their self-efficacy and quality of life. On the other hand, religion is particularly attuned to helping people recognize and cope with what they cannot control. Religion provides a transcendent framework that contains resources such as spiritual support, rituals, and rites of passage for dealing with incomprehensible and uncontrollable experiences (Pargament, 1997). These differing views of and ways of addressing control place religion and psychology at odds and likely contribute to the lack of spiritually-sensitive mental health treatments.

Third, psychologists receive little or no training on religion and spirituality. A survey of training directors of U.S. counseling programs indicated that only 18% of the graduate programs offered a course focused on religion or spirituality (Schulte, Skinner, & Claiborn, 2002). In addition, only 13% of training directors of clinical psychology programs in the U.S. and Canada indicated that their graduate programs offered a religion or spirituality course (Brawer, Handal, Fabricatore, Roberts, & Wajda-Johnston, 2002). Therefore, most mental health professionals leave graduate school unprepared to address the spiritual and religious issues of their patients. Justification of Integration

The lack of integration of spirituality into mental health treatment is counterintuitive in many ways. First, psychology is known for helping individuals with their problems. Similarly, the world religions have focused for centuries on human suffering and its amelioration (Pargament, 1997). Second, the discomfort of many practitioners around spirituality in psychotherapy contradicts the basic tenets of psychology. »It is paradoxical that traditional psychology and psychotherapy, which fosters individualism, free expression, and tolerance of dissent, would be so reluctant to address one of the most fundamental concerns of humankind-morality and spirituality« (Bergin & Payne, 1991, p. 201). Third, the views of psychology and religion regarding control can be seen as complimentary rather than contradictory. Individuals are likely to benefit from an awareness of both their capacities and limitations, rather than one to the exclusion of the other (Pargament, 1997). Fourth, there is considerable evidence that people draw on their spirituality as a resource in dealing with their problems. For example, among individuals paralyzed in severe accidents, the most common response to the question »Why me?« was »God had a reason« (Bulman & Wortman, 1977). Fifth, while spirituality can be a source of support and comfort during difficult times, it can also cause significant conflict and distress. Psychological problems are often accompanied by spiritual struggles that can have significant implications for long-term health and well-being (Trevino, K. M., Pargament, K. I., Cotton, S., Leonard, A. C., Hahn, J., Caprini, C. A., & Tsevat, J., in press; McConnell, K. M., Pargament, K. I., Ellison, C. G., & Flannelly, K. J., 2006). Therapists who overlook the spiritual nature of the problem may be neglecting a dimension that is critical to the solution. Sixth, spirituality cannot be fully separated from psychotherapy. Even presumably secular therapies have been shown to impact people spiritually (e.g., Tisdale et al., 1997). Moreover, many people draw on spiritual resources as adjuncts to traditional psychological treatment (see Rye & Pargament, 2002). Finally, survey studies indicate that a number of individuals desire spiritually-integrated treatment. For example, in a study across six mental health centers, 55% of clients reported a desire to discuss their religious or spiritual concerns in counseling (Rose, Westefeld, & Ansley, 2001).

In short, there are many good reasons to take spirituality seriously in psychotherapy. For that to happen, however, psychotherapists need a way to understand spirituality that can guide their work. Current models of spirituality do not provide a useful frame of reference for understanding and addressing spiritual issues in clinical practice. Most notably, much of the research in the psychology of religion has reduced religion and spirituality to other functions, such as social support, meaning in life, psychological traits, or physiology. The problem with such frameworks of spirituality is that they are not sensitive to individuals who believe that their faith reflects true reality. They fail to consider the possibility that spirituality has a unique quality in itself that cannot be fully reduced to other, more secular, factors. By »unique quality«, we are not speaking to the ontological truths of beliefs in God or other religious claims. Rather, we are raising the possibility that perceptions of beliefs about, emotions toward, and relationships with what the individual holds sacred play a distinctive role in life. The purpose of this paper is to offer clinicians a non-reductionistic way to understand and evaluate spirituality. With this framework, clinicians will be better equipped to address spiritual issues in mental health treatment. Framework for Understanding Spirituality

We begin by considering some definitional issues. Religion and spirituality have been defined in many ways and these definitions have changed repeatedly over the past 40 years (see Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005). Traditionally, religion was defined broadly. However, religion has become increasingly associated with institutional organizations, rituals, and dogma while spirituality has been defined as an individual experience of the divine. Moreover, religion is increasingly seen as »bad« and spirituality as »good;« a perspective that may reflect cultural shifts toward individualism and antagonism for traditional authority. Given the changing landscape of conceptualization of religion and spirituality, it is important to offer a clear definition of these constructs. The term religion will be used to refer to the social, institutional and cultural, context of spirituality. Spirituality will be defined as »a search for the sacred« (Pargament, 1999, p.12). Spirituality is, from this point of view, the most central function of religion. There are two terms that are key to the definition of spirituality: sacred and search.

The Sacred Domain

Sacred Core

At the core of the sacred is God, the divine, or transcendent reality (Pargament, 2007). These constructs are difficult to define and most religious traditions depict God or the divine as mysterious and ineffable. In addition, individuals from different traditions, experiences, and cultures have diverse understandings of the sacred core. Sacred Ring

There is more to the sacred than this core. Surrounding the core are aspects of life that become sacred through their association with the divine. Sanctification is the process through which secular aspects of life are imbued with divine significance (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). This process can occur in two ways. First, individuals can perceive an object or experience as an expression of the divine or manifestation of God. Second, objects can be imbued with qualities that are often associated with the divine, such as transcendence, timelessness, and ultimacy (Pargament, 2007, p. 38). Sacred objects point to a deeper, timeless dimension of life, one that people hold to be »really, real.« Search for the Sacred

The definition of spirituality as a search for the sacred rests on the assumption that individuals strive for goals in their lives (see Emmons, 1999). This assumption departs from the more common psychological assumption that humans are the products of internal and/or external forces. However, psychology’s reactive view is limited and does not account for individuals' ability to investigate, plan for the future, and generate and implement plans to achieve goals. In addition, the reactive view of human nature interferes with change by failing to account for individuals' freedom and ability to choose. One of the most important and consequential of all choices has to do with one’s goals and destinations in life. When making these decisions, people seek objects that are significant to them. One significant object that many people strive for is the sacred.

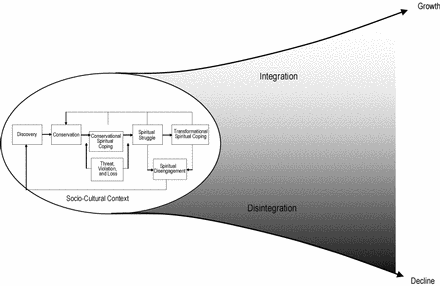

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the process of the search for the sacred (Pargament, 2007). In the following sections, we provide a brief overview of the search for the sacred followed by a more in-depth description of each phase of this process and ways the search for the sacred can differ across individuals.

Figure 1: The search for the sacred

The search for the sacred is dynamic and evolving, not fixed and static. It begins with an individual’s discovery of the sacred. After finding the sacred, the individual takes a spiritual path to sustain and cultivate his or her relationship with the sacred. However, the individual may experience life events that violate, threaten, harm, or reveal limits of the sacred. The individual must then cope to preserve and protect the sacred. In spite of these efforts, there are times when internal and external pressures disrupt an individual’s spiritual world and create spiritual turmoil. These spiritual struggles can be brief, followed by a return to previous spiritual paths, or they can lead to temporary or permanent disengagement from the sacred. Spiritual struggles can also lead to fundamental transformations in the character of the sacred. Following a transformation or rediscovery of the sacred, the individual returns to conservation and the effort to build and maintain a relationship with the sacred. The search for the sacred continues over the life-span and unfolds within the individual’s situational, social, cultural, and psychological context. No two spiritual journeys are exactly alike. People come to understand the sacred and approach the sacred in myriad ways that evolve differently over time. In the following sections, we describe each phase of this search in greater detail. Discovery of the Sacred

People discover the sacred at different times and in different ways. Some people discover the sacred in childhood and maintain that connection throughout their lives. Others discover the sacred in childhood but subsequently lose touch with the sacred only to rediscover it as adults. Still others may discover the sacred for the first time late in life.

For some people, the sacred erupts into their lives as a revelation.

The sky was very blue. It was a cold day-sharp, crisp. I was in my car. I was driving east on I-40, and all of a sudden I knew it. It just happened. I mean it was just »Bam!« There it was. I can’t explain it to you in adequate words. I felt incredible warmth. I felt that there was a presence in the car with me. I felt incredible acceptance, love, a sense of well-being, euphoria, everything’s going to be well. I choose to believe, and I chose to believe at that time, that the presence that was in the car was Jesus Christ. (Miller & C’de Baca, 2001, p. 87)

Other people discover the sacred proactively by seeking and reaching out to God. The discovery of the sacred may also occur as a combination of these two processes in which God enters the individual’s life only after he or she has invited Him.

The process of discovery can occur from »inside to outside« or from »outside to inside« (Pargament, 2007, p. 63). Many people first experience a direct encounter with the sacred core and then experience the radiation of sacredness from this core to other aspects of life. Other people first experience the sacred in what were ordinary aspects of life and only then come to an understanding of the transcendent in the sacred core. The differences between these two roads to discovery are captured by Smith (1962) who stated »Handel was able to write 'The Messiah' in part because he had the faith that he had. I have the faith that I have in part because Handel wrote 'The Messiah'« (p. 186). Roots of Discovery

The discovery of the sacred is rooted in two types of factors: external and internal factors. The search for the sacred is not »noncontextual;« it occurs within a wider environment that includes life experiences, family, community, institutions, and culture. These external factors may encourage or discourage an individual’s search. In either case, external factors impact whether the individual discovers, fails to discover, or rejects the sacred, and the individual’s representation of the sacred. The process of discovery is also influenced by internal factors such as a personal yearning for the sacred. As previously stated psychologists have traditionally examined the psychological, social, and physical roots of spirituality and often reduce the search for the sacred to a pursuit of non-spiritual needs. While this may be true in some cases, the sacred may also be a significant end in itself. Consequences of Discovery

The discovery of the sacred has powerful and important consequences for an individual’s life. First, discovery of the sacred elicits spiritual emotions. These emotions are distinctive, complex, hard to describe, and both positive and negative (Otto, 1928). Positive emotions include feelings of unity and cohesion (Hood, 2005), awe and elevation (Haidt & Keltner, 2003), and gratitude, appreciation, and thankfulness (Emmons, 2000; McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002). Negative emotions may include fear, repulsion, and dread (Otto, 1928).

A second consequence of discovering the sacred is that the sacred becomes an organizing force in an individual’s life (Emmons, 1997). As people discover the sacred and experience spiritual emotions, the sacred becomes a priority in their lives and they begin to invest more of themselves into their search for the sacred. For example, research indicates that people place more effort into reaching their highly sanctified goals than their less sanctified goals (Mahoney et al., 2005). As the sacred becomes a higher priority, it integrates competing thoughts, feelings, and actions and provides direction for daily life. Third, following the discovery of the sacred, sacred objects become resources of strength and comfort. These objects create a context of meaning for life and connect people to the past, future, and each other. Sacred resources are not temporary but can be accessed throughout an individual’s life. Conserving the Sacred

The search for the sacred does not end with discovery. Once individuals discover the sacred, they strive to maintain and enhance their relationship with the sacred (Pargament, 2007). There are many pathways to conserving the sacred. People can follow pathways established by religious traditions or create their own nontraditional pathways. All pathways to the sacred are constructed out of human thoughts, relationships, behaviors, and experiences, but they are distinguished by their sacred form and content and their focus on sacred destinations.

One method of conserving the sacred is the pathway of knowing. Religious texts address fundamental questions such as how the world was formed, how people were created, the purpose of life, the meaning of tragedy, and life after death. Studying these texts helps individuals understand and make sense of life and live more consistently within the sacred domain. Individuals may also use reason and intuition to achieve knowledge of the sacred. They may gain knowledge through soul-searching, considering the perspectives of modern spiritual writers, or even scientific investigation.

A second pathway to conserving the sacred involves the application of spiritual knowledge through ritual and practice. From a spiritual perspective, religious rituals are a way to connect with the sacred. Through the use of symbols (e.g., objects, smells, sounds, and shapes), rituals allow the individual to re-create and enter a sacred domain where they can re-experience a connection with the transcendent. For example, through communion, Christians participate in Jesus’s sacrifice and receive spiritual nourishment. In the Passover Seder, Jews participate in the redemption of the Hebrew people from slavery. However, rituals are not the only spiritual action that conserves the sacred. Most religious traditions have ethics, commandments, and practices that inform believers of appropriate and inappropriate ways of living. Following these commandments brings the individual closer to the sacred and gives ordinary activities a sacred quality. Individuals can also create their own spiritual practices that bring them closer to the sacred.

Third, people can conserve the sacred through the pathway of relating to others. After discovering the sacred, most people share their spiritual perspectives with others. These relationships often unfold in the context of religious institutions where people can gather with others in worship services, prayer groups, Bible studies, and religious education. People also participate in spiritual groups outside of religious institutions, such as spiritual retreats and yoga groups (Spilka, Hood, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 2003). Finally, the sacred can be present in daily relationships with family, friends, coworkers, and community members. These relationships provide individuals with a context to share and live out their spiritual truths.

A fourth pathway to conserving the sacred is one of experiencing or having an immediate encounter with the sacred. Prayer is perhaps the most common way of experiencing the sacred. It can take many forms: silent, chanted, or spoken aloud; individually or in a group; focusing on suffering, joy, or gratitude. However, common to all forms of prayer is the ability to commune with and experience the sacred. There are other ways to experience the sacred that are not based on a theistic view of God. For example, individuals may experience encounters with angels or departed loved ones or may experience the transcendent through meditation as a way to personal enlightenment. Through these experiences, individuals conserve their relationship with and become closer to the sacred.

The metaphor of the pathway provides a concise way to describe how people can conserve the sacred. However, this metaphor may be misleading. First, the metaphor may suggest that individuals follow a concrete road toward the sacred from which they never deviate. While some individuals may follow the same spiritual path their entire lives, most spiritual pathways change and evolve as individuals encounter new life experiences and mature. Second, the pathway metaphor may suggest that the spiritual journey has a fixed and final destination. Yet, for most people, the goal of the spiritual journey is not merely to encounter the sacred. Instead, people seek an ongoing and continuous relationship with the sacred. Once discovered, the relationship must be cultivated and nurtured over time.

The discussion of spiritual pathways leads to the question of their effectiveness. Empirical studies indicate that measures of religious and spiritual beliefs, practices, relationships, and experiences are, by and large, associated with positive psychological, social, and physical outcomes including life satisfaction, greater social support and less loneliness, lower rates of depression, suicide, anxiety, and psychosis, lower rates of substance use, greater marital satisfaction, and longevity (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). In addition, these spiritual pathways help people reach spiritual goals. For example, 97% of participants who read the Bible reported that it made them feel »somewhat« or a »great deal« closer to God (Gallup & Lindsay, 1999). As we will see, however, the search for the sacred is not always effective. In Times of Stress

For most people, the search for the sacred is not a smooth, uninterrupted journey. Events occur that violate sacred objects, spiritual pathways, and views of the sacred. Desecration is the perception that a sanctified object has been violated (Magyar, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2000). Desecrations are more than traumatic events; they are violations of the transcendent or divine character of an individual’s life and worldview. Such violations can elicit feelings of anger and rage (Pargament, Magyar, Benore, & Mahoney, 2005). Life events can also be experienced as sacred losses. Sacred loss is the perception that a sanctified object has been lost (Magyar, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2000). These events tend to evoke feelings of sadness and depression (Pargament, Magyar, Benore, & Mahoney, 2005). However, sacred losses and desecrations have also been associated with spiritual growth (Magyar, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2000; Pargament, Magyar, Benore, & Mahoney, 2005). The outcome of desecrations and sacred losses depends, in part, on the individual’s ability to cope with the event. Individuals will go to great lengths to conserve their views of the sacred and their spiritual beliefs and practices in the face of sacred loss and desecration (Pargament, 2007). Conservational Spiritual Coping

One conservational method of spiritual coping is spiritual meaning-making. For many individuals, religion provides answers to life’s most difficult questions, such as why unjust events happen to just people. Spiritual meaning-making allows individuals to see traumatic events in a context that offers hope, beneficence, and an on-going relationship with the sacred. For example, traumas can challenge an individual’s view of God as a loving, protective, and all-powerful being. However, through spiritual meaning-making, these events can be viewed as spiritual tests and opportunities to grow closer to the sacred. Research indicates that spiritual meaning-making is associated with beneficial outcomes including lower levels of anxiety and depression and greater purpose in life (Mickley, Pargament, Brant, & Hipp, 1998), more effective coping techniques (Taylor, Lichtman, & Wood, 1984), and general well-being (Farber, Mirsalimi, Williams, & McDaniel, 2003).

A second method of conservational spiritual coping is seeking spiritual support and connection. During difficult times, many people turn to the sacred for support. This support may come from the perception of a direct encounter with the sacred (Pruyser, 1968). For example, a woman hospitalized for depression describes her experience with the sacred:

That night I stood with other patients in the grounds waiting to be let in to our ward. It was a very cold night with many stars. Suddenly someone stood beside me in a dusty brown robe and said, »Mad or sane you are one of my sheep.« I never spoke to anyone of this but ever since it has been the pivot of my life. I realize that the form of the vision and the words I heard were the result of my education and cultural background but the voice, though closer than my own heartbeat, was entirely separate from me (Hardy, 1979, p. 91)

Individuals may also experience spiritual support through prayer, meditation, relationships with clergy or congregation members, rituals, and worship service attendance. Although research indicates that the experience of spiritual support is associated with physical, psychological, and social benefits (Heiligman, Lee, & Kramer, 1983; Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2002), it is important to recognize that spiritual support is designed to help people conserve their relationship with the sacred itself.

A third method of spiritual coping involves rituals of purification. These rituals are applied when people commit acts that are perceived offenses against the divine, such as greed, pride, lust, murder, adultery, and hate. Rituals of purification are conservational methods of spiritual coping that allow individuals to repair their relationship with the sacred (Gray, 1998; Hymer, 1995). These rituals include acts of sacrifice, repentance, punishment, cleansing, and liturgies of atonement (see Paden, 1988 for a review). In Western culture, spiritual confession is one of the most common purification rituals and is practiced by most religious groups. Confessions may be public or private and include acknowledgement that the individual has committed a spiritual violation and a request for forgiveness (Swank, 1992). Most importantly, spiritual confessions provide individuals with a resource for restoring the damaged relationship between themselves and the divine.

The experience of Dick, a recovering alcoholic working through the stages of AA, illustrates the therapeutic value of spiritual confession. Dick completed Step Four of the AA program by making a »searching and fearless moral inventory« (Jensen, 2000, p. 54) of himself. As a result of this search, he created a list of his transgressions and felt ready to begin Step Five with a confession to God. Toward this end, he arranged a meeting with his pastor.

I went down there. And I carried that list that I had and laid it on his desk…And I sat down and started talking. I let him have it. I guess I talked to him about an hour and a half. So when I got through, I stood up. And he said, »Are you through?« And I said, »Yea.«…He said, »You want this piece of paper?« I said, »Na.« He tore it up. Threw it in the trashcan. Now, then something came over me. I started walkin' on air. And I felt a sense of freedom that I never felt before in my life. (Jensen, 2000, p. 55)

These methods of conservational spiritual coping illustrate some of the ways people can draw on their spiritual resources to sustain their relationship with the sacred when it has been violated or harmed. Research indicates that these spiritual coping methods are associated with health and well-being in various samples (see Pargament, 1997, 2007 for a review). A meta-analysis of 49 studies found that positive religious coping strategies were associated with better psychological adjustment (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005). Spiritual coping methods have also been shown to be effective in helping individuals conserve the sacred. For example, research indicates that individuals maintain their level of involvement in religious activities during crises (see Pargament, 1997) and that spiritual coping is often associated with spiritual growth and well-being (Pargament, Koenig, Tarakeshwar, & Hahn, 2004). Transformational Spiritual Coping

As previously stated, some life events disrupt an individual’s view of and relationship with the sacred to such an extent that conservation of the sacred is not possible. At these times, previous understandings of the sacred and pathways to the sacred are no longer viable and individuals must struggle to find new ways of understanding and finding the sacred. Spiritual struggles are expressions of conflict, question, and doubt regarding matters of faith, God, and religious relationships (Pargament, Murray-Swank, Magyar, & Ano, 2005). They can be differentiated from other forms of spiritual coping by the spiritual stress that emerges within the coping process. In response to spiritual struggles, individuals attempt to reorient themselves by developing new understandings of and new pathways to reach the sacred.

Spiritual transformation consists of fundamental changes in the place of the sacred in an individual’s life, the character of the sacred, and pathways an individual takes to reach the sacred (Pargament, 2006, 2007). The methods of spiritual transformation are diverse and can come from religious traditions or can be created by the individual him/herself. Consider three transformational methods of spiritual coping. First, spiritual rites of passage often accompany events such as births, coming of age, marriage, role changes, and death. These transitions often call for a change in the individual’s core identity. Rites of passage are designed to facilitate this transformation. For example, funeral services mark the transition of a community member from life to death and the new role of the individual’s loved ones as mourners. Prayers and rituals to help the deceased transition to the afterlife are often incorporated into the service. The funeral service also includes symbols of the new role of the bereaved including particular attire and visits from friends and family. Rites of passage underscore the fact that a significant event has occurred, one that is forcing the individual to move from one sacred status to another.

Revisioning the sacred is another method of transformational spiritual coping. Images of God created in childhood may not stand up to the range of experiences and challenges of an individual’s life. For example, a view of God as loving and all-powerful may be difficult to reconcile with experiences of injustice and suffering. In this case, an individual may transform his or her view of God from a loving and all-powerful Being to a loving but limited God (Kushner, 1981). Similarly, an individual who views God as distant or punitive may begin to view the divine as a compassionate Being who is present during times of pain and difficulty. For example, Jones (1991) described a female client, Sylvia, who experienced God’s forgiveness in therapy through a change in her image of God. Sylvia began therapy feeling guilty for past transgressions and isolated from her family and from God. She viewed God as judgmental and impatient. As therapy progressed, her views of God and her relationship with God began to change. Slowly, she began to view God as accepting and caring. By the end of therapy, Sylvia was able to see God as forgiving and to experience that forgiveness. «'I see,' Sylvia said, 'that God’s love is greater than my mistakes'« (Jones, 1991, p. 73).

Transforming the sacred can also occur through realignment of the sacred within an individual’s priorities or hierarchy of significant values. In this transformational method of spiritual coping, the sacred may be moved from a distal position in the individual’s life to the center. The divine becomes the focal point of the individual’s life and definition of the self. There are three steps involved in this process of centering the sacred. First, the individual must recognize the limitations of his or her current values and strivings. For some people, a powerful experience, such as confrontation with death, will lead to a change in their priorities. However, other individuals require repeated failed attempts to conserve their strivings before they realize they are »striving at a wrong angle« (Starbuck, 1899, p. 115).

Second, an individual must let go of his/her old values and strivings. This aspect of the process is difficult because these strivings provide organization and meaning to life, even if they are problematic in other respects. Spiritual resources can assist individuals with this aspect of the process of centering the sacred. For example, meditation helps individuals detach from destructive goals. Prayer can also help individuals resist the temptation of destructive strivings and remain focused on the sacred. Research on spiritual surrender indicates that letting go of old strivings is associated with less depression, better quality of life, and more stress-related growth (Koenig, Pargament, & Nielsen, 1998). However, letting go creates a vacuum in the individual’s life that must be filled with other sources of significance.

The third step in this process is placing the sacred in the vacuum at the center of the individual’s life. When this occurs, the sacred becomes the defining aspect of an individual’s identity. Movement of the sacred from the periphery to the center of life may occur gradually through introspection and self-discipline or rapidly as the result of a sacred experience or encounter. Placing the sacred at the center is a radical transformation of values and significance (Miller & C’de Baca, 2001).

Religion is the center of my life now. It’s not compartmentalized, like just going to church on Sunday. My church life is all through everything I do. I consider what Scripture says or try to consider what Scripture says about all decisions in my life: in the way I raise my children, in the way I relate to my wife, the way I relate to my employer. (Miller & C’de Baca, 2001, p. 117)

Although born out of a stressful experience, this transformation can strengthen and empower people in the pursuit of new strivings. For example, a comparison of college students who had and had not become more religious over the previous two years indicated that individuals who had become more religious reported improvements in self-esteem, self-confidence, and personal identity and greater closeness to God (Zinnbauer & Pargament, 1998). However, it is also important to recognize that transformational spiritual coping can lead to spiritual disengagement or a lost of interest in the sacred (Pargament, 2007). Spiritual disengagement is characterized by disconnection from God, the transcendent, or a religious community. For some people, spiritual disengagement is the end of the search for the sacred. However, for others, the desire for the sacred is not completely extinguished and the search for the sacred can be rekindled later in life. Evaluating Spirituality: Integration and Dis-Integration

Spirituality, as described here, is a normal and natural part of life. However, as we have discussed, the search for the sacred does not always proceed smoothly and an individual’s spirituality can become a source of problems. Thus, no model of spirituality, particularly a clinical model of spirituality, would be complete if it did not attend to the thorny issue of evaluation. One way to evaluate the merits of an individual’s spirituality is to consider the degree to which his/her spirituality is well-integrated (see Figure 1; Pargament, 2007). A well-integrated spirituality is one whose components work together in harmony and synchrony. It is made up of pathways that are broad, deep, and responsive to the full range of life situations. It is also supported by the larger social context and capable of both continuity and change. A well-integrated spirituality moves toward a sacred destination that encourages human potential and provides people with a powerful guiding vision. In contrast, a dis-integrated spirituality is marked by conflicts among its component parts. It lacks scope and depth, and is unable to respond to the demands of life situations. It changes too easily or not at all. In addition, it is directed toward a sacred end that restricts human possibilities and fails to provide individuals with a compelling purpose in life. As they wrestle with evaluative issues of this kind, practitioners are now beginning to address the spiritual dimension in psychotherapy.

Practical Examples and Implications

Spiritually integrated interventions have shown some promising results. For example, several psychospiritual programs have been developed to meet the needs of HIV/AIDS patients. One such intervention is »Lighting the Way: A Spiritual Journey to Wholeness.« This is a nondenominational group intervention for women with HIV that addresses existential issues, such as healing, isolation, anger, and guilt (Pargament, McCarthy, et al., 2004). It also incorporates discussions of spiritual resources and spiritual struggle. Preliminary assessment of a comparable intervention indicated that participants experienced increases in self-rated religiosity and positive religious coping and decreases in spiritual struggle and depression over the course of the intervention (Tarakeshwar, Pearce, & Sikkema, 2005). In another intervention, participants were taught to repeat a silent mantram, a word or phrase with a spiritual association, throughout the day. Participation in the intervention was associated with declines in intrusive thoughts and anger and improvements in quality of life and spirituality (Bormann et al., 2006). Finally, Avants, Beitel, and Margolin (2005) developed a program entitled Spiritual Self-Schema (3-S Therapy). Drawing on meditative practices and Buddhist philosophy, this program is designed to increase motivation for HIV prevention among drug users. Initial results indicate that 3-S Therapy increases motivation to prevent HIV, reduces HIV risk behavior, and reduces drug use (Avants, Beitel, & Margolin, 2005; Margolin, Beitel, Schuman-Olivier, & Avants, 2006). Taken as a whole, the findings from these interventions suggest that psycho-spiritual treatments can be relevant and beneficial to individuals with HIV/AIDS.

Interventions for other populations have also been developed. For example, Cole and Pargament (1999) developed a psycho-spiritual intervention for cancer survivors that targets spiritual struggles by encouraging participants to explore feelings of abandonment by and anger towards God. This psycho-spiritual intervention was compared to a no-treatment control condition (Cole, 2005). Results indicated that pain severity remained stable from pre-treatment to post-treatment for the psycho-spiritual group but increased in the control group. In addition, depression remained stable over an eight-week follow-up in the psycho-spiritual group but increased in the control group. In addition, Murray-Swank and Pargament (2005) developed an eight-week, manualized psycho-spiritual intervention for female survivors of sexual abuse that targets spiritual struggles, including feelings of divine abandonment and anger toward God. Four of the five participants in the intervention reported significant reductions in psychological distress over the course of the intervention and at follow-up. Finally, an eight-week group treatment for Mormon undergraduates dealing with perfectionism integrated Mormon teachings with cognitive-behavioral methods. From pre- to post-treatment, participants reported significant declines in perfectionism and depression and significant improvements in self-esteem, religious well-being, and existential well-being (Richards, Owen, & Stein, 1993).

These psycho-spiritual interventions are merely a sample of interventions designed to incorporate and address individuals' spirituality into psychological treatment. Initial evaluation of these interventions indicates that they can effectively reduce psychological distress and promote spiritual growth. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest that spiritually integrated interventions are more effective than secular interventions. For example, in a direct comparison of spiritual and secular meditation, spiritual meditation was more effective at reducing headache pain in college students than secular meditation and progressive relaxation (Wachholtz & Pargament, in press). In a study of women with eating disorders in an inpatient setting, participants were divided into three conditions: a spiritual group read a spiritual workbook and discussed the readings, a cognitive group read a cognitive-behavioral self-help workbook and discussed the readings, and an emotional support group discussed nonspiritual topics such as self-esteem and nutrition. All participants improved over the course of treatment. However, participants in the spiritual group showed significantly greater improvement in eating attitudes and spiritual well-being and greater declines in symptom distress, relationship distress, and social role conflict than participants in the other conditions (Richards, Berrett, Hardman, & Eggett, 2006). Although limited in number, other studies have indicated that psycho-spiritual interventions are equally and perhaps more effective than secular interventions (see Pargament, 2007 for a review). However, there are inconsistencies in the literature and further research is necessary before definitive conclusions can be made regarding the efficacy of psycho-spiritual treatments.

In this paper, we have presented a theoretical model of spirituality. It is admittedly dynamic, fluid, and complex. However, we maintain that these are qualities of spirituality itself. Therapists will be unable to address the spiritual dimension in psychotherapy unless they can understand and evaluate spirituality in all of its richness and complexity. Our model of spirituality also represents an alternative to reductionistic explanations of spiritual life. This model rests on the assumption that, on many occasions, unless clinicians are able to appreciate spirituality as a dimension of life that can be significant in and of itself, they will be unlikely to form effective working relationships with their clients, many of whom are convinced of the ontological truth of their worldview. In short, it is our hope that this theoretical model of spirituality will assist practitioners in the development of a more comprehensive and holistic approach to mental health care.

References

Ano, G.A. & E.B. Vasconcelles (2005): Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 1-20.

Avants, S.K., M. Beitel & A. Margolin (2005): Making the shift from »addict self« to »spiritual self«: Results from a Stage I study of spiritual self-schema (3-S) therapy for the treatment of addiction and HIV risk behavior. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 8, 167-177.

Bergin, A.E. & I.R. Payne (1991): Proposed agenda for a spiritual strategy in personality and psychotherapy. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 10, 197-210.

Bormann, J.E., D. Oman, J.K. Kemppainen, S. Becker, M. Gershwin & A. Kelly (2006): Mantram repetition for stress management in veterans and employees: A critical incident study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 53, 502-512.

Brawer, P.A., P.J. Handal, A.N. Fabricatore, R. Roberts & V.A. Wajda-Johnston (2002): Training and education in religion/spirituality within APA-accredited clinical psychology programs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 203-206.

Bulman, R.J. & C.B. Wortman (1977): Attributions of blame and coping in the »real world«: Severe victims react to their lot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 351-363.

Cole, B.S. (2005): Spiritually-focused psychotherapy for people diagnosed with cancer: A pilot outcome study. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 8, 217-226.

Cole, B.S. & K.I. Pargament (1999): Spiritual surrender: A paradoxical path to control. In W.R. Miller (Ed.), Integrating spirituality into treatment: Resources for practitioners (179-198): Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Emmons, R.A. (1999): The psychology of ultimate concerns: Motivation and spirituality in personality. New York: Guildford Press.

Emmons, R.A. (2000): Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 56-69.

Farber, E.W., H. Mirsalimi, K.A. Williams & J.S. McDaniel (2003): Meaning of illness and psychological adjustment to HIV/AIDS. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry, 44, 485-491.

Gallup, G. Jr. & D.M. Lindsay (1999): Surveying the religious landscape: Trends in U.S. beliefs. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse.

Gray, K. (1998): Sacraments of healing: A return from exile and a healing of heart. In S. Hahn & L. J. Suprenant (Eds.), Catholic for a reason: Scripture and the mystery of the family of god (261-284): Steubenville: Emmaus Road Publishing, Inc.

Haidt, J. & D. Keltner (2003): Appreciation of beauty and excellence. In C. Peterson & M.E.P. Seligman (Eds.), Character strengths and virtues (537-551): Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hardy, A. (1979): The spiritual nature of man: A study of contemporary religious experience. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Heiligman, R.M., L.R. Lee & D. Kramer (1983): Pain relief associated with a religious visitation: A case report. Journal of Family Practice, 16, 299-302.

Hood, R.W., Jr. (2005): Mystical, spiritual, and religious experiences. In R. F. Paloutzian & C.L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (348-364): New York: Guilford Press.

Hymer, S. (1995): Therapeutic and redemptive aspects of religious confession. Journal of Religion and Health, 34, 41-55.

Jensen, G. H. (2000): Storytelling in alcoholics anonymous: A rhetorical analysis. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Jones, J. (1991): Contemporary psychoanalysis and religion: Transference and transcendence. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Koenig, H.G., M.E, McCullough & D.B. Larson (2001): Handbook of religion and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Koenig, H.G., K.I. Pargament & J. Nielsen (1998): Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 513-521.

Kushner, H. (1981): When bad things happen to good people. New York: Schocken Books.

Lindgren, K.N. & R.D. Coursey (1995): Spirituality and serious mental illness: A two-part study. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 18, 93-111.

Magyar, G.M., K.I. Pargament & A. Mahoney (2000, August): Violating the sacred: A study of desecration among college students. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Mahoney, A., K.I. Pargament, B. Cole, T. Jewell, G. Magyar-Russell, N. Tarakeshwar et al. (2005): A higher purpose: The sanctification of strivings in a community sample. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15, 239-262.

Margolin, A., M. Beitel, Z. Schuman-Olivier & S. K. Avants (2006): A controlled study of a spiritually-focused intervention for increasing motivation for HIV prevention among drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18, 311-322.

McConnell, K. M., K. I. Pargament, C. G. Ellison & K. J. Flannelly (2006): Examining the links between spiritual struggles and psychopathology in a national sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1469-1484.

McCullough, M.E., R.A. Emmons & J. Tsang (2002): The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112-222.

Mickley, J.R., K.I. Pargament, C.R. Brant & K.M. Hipp (1998): God and the search for meaning among hospice caregivers. Hospice Journal, 13, 1-17.

Miller, W.R. & J. C’de Baca (2001): Quantum change: When epiphanies and sudden insights transform individual lives. New York: Guilford Press. Murray-Swank, N.A. & K.I. Pargament (2005): God, where are you?: Evaluating a spiritually-integrated intervention for sexual abuse. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 8, 191-204.

Otto, R. (1928): The idea of the holy: An inquiry into the nonrational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational (J.W. Harvey, Trans.). London: Oxford University Press. (Originally published 1917)

Paden, W.E. (1988): Religious worlds: The comparative study of religion. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pargament, K.I. (1997): The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

Pargament, K.I. (1999): The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 9, 3-16.

Pargament, K.I. (2006): The meaning of spiritual transformation. In J.D. Koss-Chioino & P. Hefner (Eds.), Spiritual transformation and healings: Anthropological, theological, neuroscientific, and clinical perspectives (10-24). Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Pargament, K.I. (2007): Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York: The Guilford Press.

Pargament, K.I., H.G. Koenig, N. Tarakeshwar & J. Hahn (2004): Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical, and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 713-730.

Pargament, K.I., G.M. Magyar, E. Benore & A. Mahoney (2005): Sacrilege: A study of sacred loss and desecration and their implications for health and well-being in a community sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 59-78.

Pargament, K.I. & A. Mahoney (2005): Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15, 179-198.

Pargament, K.I., S. McCarthy, P. Shah, G. Ano, N. Tarakeshwar, A.B. Wachholtz et al. (2004): Religion and HIV: A review of the literature and clinical implications. Southern Medical Journal, 97, 1201-1209.

Pargament, K.I., N. Murray-Swank, G.M. Magyar & G. Ano (2005): Spiritual struggle: A phenomenon of interest to psychology and religion. In W.R. Miller & H. Delaney (Eds.), Judeo-Christian perspectives on psychology: Human nature, motivation, and change (245-268). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Phillips, R.E. III, R. Lakin & K.I. Pargament (2002): The development of a psychospiritual intervention for people with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 38, 487-495.

Post, S.G., C.M. Puchalski & D. B. Larson (2000): Physicians and patient spirituality: Professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Annals of Internal Medicine, 132, 578-583.

Prest, L.A. & J.F. Keller (1993): Spirituality and family therapy: Spiritual beliefs, myths, and metaphors. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 19, 137-148.

Pruyser, P.W. (1968): A dynamic psychology of religion. New York: Harper & Row.

Richards, P.S., M.E. Berrett, R.K. Hardman & D.L. Eggett (2006): Comparative efficacy of spirituality, cognitive, and emotional support groups for treating eating disorder inpatients. Eating Disorders: Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 41, 401-415.

Richards, P.S., L. Owen & S. Stein (1993): A religiously oriented group counseling intervention for self-defeating perfectionism: A pilot study. Counseling and Values, 37, 96-104.

Rose, E.M., J.S. Westefeld & T.N. Ansley (2001): Spiritual issues in counseling: Clients' beliefs and preferences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 61-71.

Rye, M., & K.I. Pargament (2002): Forgiveness and romantic relationships in college: Can it heal the wounded heart? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 419-441.

Schulte, D.L., T.A. Skinner & C.D. Claiborn (2002): Religious and spiritual issues in counseling psychology programs. Counseling Psychologist, 30, 118-134.

Shafranske, E.P. (2001): The religious dimension of patient care within rehabilitation medicine: The role of religious attitudes, beliefs, and personal and professional practices. In T.G. Plante & A.C. Sherman (Eds.), Faith and health: Psychological perspectives (311-338). New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, K. & E.W. Schrimshaw (2002): The perceived benefits of religious and spiritual coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41, 91-102.

Smith, W.C. (1962): The meaning and end of religion. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

Spilka, B., R.W. Hood Jr., B. Hunsberger & R. Gorsuch (2003): The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Starbuck, E.E. (1899): The psychology of religion. New York: Scribner.

Swank, A.B. (1992): Spiritual confession: A theoretical synthesis and experimental study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH.

Tarakeshwar, N., M.J. Pearce & K.J. Sikkema (2005): Development and implementation of a spiritual coping group intervention for adults living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 8, 179-190.

Taylor, S.E., R.R. Lichtman & J.V. Wood (1984): Attributions, beliefs about control, and adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 46, 489-502.

Tisdale T.C., T.L. Keys, K.J. Edwards, B.F. Brokaw, S.R. Kemperman, H. Cloud et al. (1997): Impact of treatment on God image and personal adjustment, and correlations of God image to personal adjustment and object relations adjustment. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 25, 227-239.

Trevino, K. M., K. I. Pargament, S. Cotton, A. C. Leonard, J. Hahn, C. A. Caprini & J. Tsevat (in press): Religious Coping and Physiological, Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Outcomes in Patients with HIV/AIDS: Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Findings. AIDS & Behavior.

Wachholtz, A. & K. I. Pargament (in press): Does spirituality matter? Effects of meditative content and orientation on migraneurs. Journal of Behavioral Medicine.

Zinnbauer, B.J. & K.I. Pargament (1998): Spiritual conversion: A study of religious change among college students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 161-180.

Zinnbauer, B.J. & K.I. Pargament (2005): Religiousness and spirituality. In R.F. Paloutzian & C.L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (21-42): New York: Guilford Press.

Note

*FOOTNOTE_REF_1* Portions of this paper were adapted from the second author’s recent book, Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy: Understanding and Addressing the Sacred.