On the Margins: Considering Diversity among Consensually Non-Monogamous Relationships

Summary

Consensual non-monogamy (CNM) encompasses romantic relationships in which all partners agree that engaging in sexual and/or romantic relationships with other people is allowed and part of their relationship arrangement (Conley, Moors, Matsick & Ziegler, 2012). Previous research indicates that individuals who participate in CNM relationships are demographically homogenous (Sheff & Hammers, 2010; Sheff, 2005); however, we argue that this may be an artifact of community-based recruitment strategies that have created an inaccurate reflection of people who engage in CNM. To achieve a more nuanced understanding of the identities of individuals engaged in departures from monogamy, the present study provides a comparative analysis of descriptive statistics of those in CNM relationships and those in monogamous relationships. Using data from two large online samples, we examined the extent to which individuals with certain demographic variables (gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age) are over- or under-represented in CNM and monogamous relationships. Overall, we aim to promote future research of CNM that is more inclusive of diverse identities.

Keywords: consensual non-monogamy, diversity, identity

Within the past ten years, consensual non-monogamy (CNM) has gained considerable attention within academic scholarship (e.g., Barker, 2005a; Conley, Ziegler, Moors, Matsick, & Valentine, 2012; Klesse, 2007; Rust, 1996; Sheff, 2005). To date, most of the empirical research exploring CNM—relationships in which all involved partners have openly agreed that they and/or their partners will have other sexual or romantic partners—has utilized qualitative interviews, or occasionally survey methods, to elucidate how non-monogamous individuals both construct and experience their relationships (Frank & DeLameter, 2010; Klesse, 2006; Sheff, 2005; Ritchie & Barker, 2006). The results of these studies, while greatly beneficial for understanding departures from monogamy, do not adequately explicate the number of people involved in such relationships due to small sample sizes. Thus, despite growing academic interest in CNM relationships, we know of no research that has addressed the prevalence of CNM relationships (including swinging, polyamory, and open relationships).

Prevalence of CNM Relationships

During the 1970s, Blumstein and Schwartz (1983) asked more than 6,000 couples whether or not they had an agreement that allowed sex outside of their relationship. Estimates indicated that 15-28% of heterosexual married couples have an agreement that permits extramarital sex (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983). When taking into account sexual minorities, 65% of gay men and 29% of lesbian women in the sample also engaged in such relationships. The estimates based on the Blumstein and Schwartz study, however, are substantially higher than approximations provided by other researchers. Research during the same time period found that while 7% of heterosexual married couples would consider engaging in consensual non-monogamy, only 1.7% reported having an open relationship (Cole & Spaniard, 1974).

More recently, a 2002 representative sample of adults from National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) found that approximately 18% of women and 23% of men were engaged in non-monogamy (Aral & Leichliter, 2010). These percentages suggest that an estimated 19 million Americans participate in non-monogamy. However, the authors operationally defined non-monogamy as having at least one sexual partner outside of the primary relationship within the past year, with information about whether participants’ partners were aware of the current relationship left unreported. Subsequently, this definition does not embody parameters that we consider CNM (i.e., relationships in which all involved partners have openly agreed to sexual and/or romantic encounters with other individuals).

Our recent studies with United States samples have demonstrated that approximately 4% to 5% of people are currently involved in CNM relationships (Conley, Moors, Matsick, & Ziegler, 2011, 2012; Moors, Edelstein, Conley, & Chopik, under review). In these studies, we used general online recruitment strategies (i.e., cases in which recruitment was not targeted for CNM individuals or any other identity) to garner participants. Although these estimates are the first to consider individuals in multiple types of CNM arrangements (i.e., swinging, polyamory, and open relationships), these statistics do not elucidate who engages in CNM. In an effort to provide a more nuanced understanding of the identities of individuals engaged in CNM, the present study will consider demographic characteristics of those in CNM relationships compared to monogamous relationships. In the next section, we will address our operationalization of CNM as well as different CNM arrangements.

Consensual Non-monogamous Arrangements

Although we acknowledge that this special issue is dedicated to polyamory, we refer to any relationship arrangement in which the partners openly agree to have more than one sexual or romantic relationship(s) as CNM. Diverse approaches to CNM exist, including but not limited to polyamory (engaging in consensual romantic relationships with more than one person; Barker, 2005b; Klesse, 2007), swinging (an arrangement in which both partners engage in extradyadic sex, usually in a social setting in which both partners are in attendance; Jenks, 1998), and open relationships (relationships in which partners pursue independent sexual relationships outside of a primary dyad; Hyde & DeLamater, 2000). While previous research has concentrated on a specific subset of CNM (i.e., polyamory or swinging) rather than investigating non-monogamy as a whole (Barker & Langdridge, 2010), we will focus on the commonalities shared amongst different kinds of consensual departures from monogamy. Moreover, we believe it is important for researchers to make an effort to embrace the diversity of ethical non-monogamous sexual practices.

The positioning of polyamory as superior to more «pleasure focused” non-monogamies (i.e., swinging and open relationships) has created normative boundaries within sexual subcultures (Frank & DeLameter, 2010). For instance, in a longitudinal study of sexual minority men and women engaged in CNM relationships, participants evoked rhetoric that differentiated between the «good polyamorist” and the «promiscuous swinger” in an effort to reinforce ideological differences between forms of non-monogamy (Klesse, 2006). To circumscribe this hierarchy, it is helpful to frame relationships on a monogamy continuum, in which some relationships fall strongly on the monogamous end of the spectrum (for example, even a thought of being attracted to another person is intolerable) whereas others fall on the consensually non-monogamous end (for example, having explicit agreements with partners to engage in more than one sexual/romantic relationship). Thus, we conceptualize consensual departures from monogamy—whether sexual or romantic in nature—as having more similarities among one another than with monogamy. In this next section, we consider the demographic characteristics of individuals engaged in CNM through a brief overview of past research.

White, Educated, and Middle Class: The Face of Consensual Non-Monogamy

While it is highly likely that there are diverse communities that engage in alternatives to monogamy, both empirical research and mainstream media reinforce a homogenous identity associated with CNM (e.g., Bennett, 2009; Nöel, 2006; Rohter, 2010; Sklar, 2010). Some research endorses CNM as an effective relationship-style for anyone (Haritaworn, Lin, & Klesse, 2006); however, despite this emphasis on diversity, the experiences of white, educated, heterosexually-paired primary partners are predominant throughout academic literature and relationship «self-help” books (Ravenscroft, 2004; Sheff & Hammers, 2011).

The burgeoning academic research on CNM reveals a population similar in race, age, income, and education. For instance, results of a 36 study meta-analysis on CNM indicate a largely homogenous population of educated, white, middle- and upper-middle-class professionals, with the percent of people of color ranging from zero to a rare high of 48% (Sheff & Hammers, 2011). Specifically, within the context of polyamory communities, Sheff (2005) found race to be the most homogenous demographic characteristic, with the majority (89%) of 81 participants identifying as white. Additional demographic characteristics reveal that participants ranged in age from their late 30’s to early 50’s, were predominantly middle or upper class, and college educated. These attributes are also commonly found in swinging communities, with 90% of swingers identifying as white, above average in education and income, and ranging in age from 28 to 45 (Jenks, 1985; Levitt, 1988).

While these statistics indicate racial homogeneity, these samples may not be representative of the array of individuals engaged in CNM relationships. Recruitment strategies for those who study CNM populations often rely heavily on snowball sampling to garner participants for qualitative interviews, participant observation, and in-person questionnaires (Sheff & Hammers, 2011). Thus, these demographic characteristics may be more representative of individuals engaged in mainstream CNM communities with extended social networks as opposed to the larger population. In an effort to understand the diversity among individuals in CNM relationships, the present study employed general recruitment strategies to examine the prevalence of CNM and monogamy across race/ethnicity and age[1].

Heterosexual and Partnered: Consensual Non-Monogamy and Sexual Orientation

Popular relationship self-help texts—although increasing visibility of sexual subcultures within the public domain—often reinforce a «monogamous-style” of relating that emphasizes the primacy of heterosexual dyadic commitment within CNM relationships (Wilkinson, 2010). Books such as Opening Up: A Guide to Creating and Sustaining Open Relationships (Taormino, 2008) and Polyamory in the 21st Century (Anapol, 2010) frame non-monogamy as an avenue to «open up” an existing relationship or marriage. While it is likely that many monogamous couples transition into CNM given monogamy is hallmark in contemporary U.S. society, there is no research to suggest that primary partnerships are the most preferred avenue for engagement in CNM. Subsequently, discourse that accentuates dyadic commitment may reify, rather than transgress, normative standards regarding sexuality, gender, and relationships.

Within empirical research, early scholarship sought to establish definitional and demographic parameters for variations in CNM. For example, several ethnographic and qualitative studies explored open marriages (O’Neill & O’Neill, 1970, 1972), co-marital sex (Smith & Smith, 1974), and group marriages (Constantine & Constantine, 1973), with findings that indicated the primacy of the heterosexual dyad in these relationship types. In more recent studies, Finn and Malson (2008) found that CNM relationships often reinforce a regulation of time, energy, and resources similar to monogamous couples through the maintenance of primary-partnerships. Barker (2005) reiterates this claim, noting that some interview participants evoke similarities between CNM and monogamy in an effort to emphasize normativity. Additionally, other scholars have suggested that CNM affirms traditional gender roles by assuming that gender equality has been achieved within society and, consequently, that women and men share equal privileges within relationships (Klesse, 2005).

The focus on heterosexual and partnered individuals in mainstream literature and some empirical research may reflect a distancing between different forms of CNM. Ritchie and Langridge (2010) note that swinging and polyamory are often perceived as a CNM possibility for heterosexual individuals, with alternatives to monogamy viewed as a normative relationship choice within gay-male culture. Although little research exists regarding the involvement of lesbians and other sexual minorities in CNM relationships (Rothblum, 2009), empirical evidence suggests that variations of non-monogamy have been present in gay male culture for at least the past fifty years (Bettinger, 2005; Bonello & Cross, 2010; Klesse, 2007; Shernoff, 2006). Some research investigating rates of CNM among gay men suggest that 50.3% identify as part of a CNM relationship (Valentine & Conley, under review). In an effort to garner a more inclusive representation of sexual minorities, the present study examined the proportion of sexual minorities and heterosexual individuals engaged in CNM and monogamy. Additionally, to better understand gender composition, we also examined the proportion of men and women engaged in both types of relationships.

Present Study

As previously discussed, research indicates that individuals engaged in CNM relationships are demographically homogenous (Sheff & Hammers, 2011; Sheff, 2005); however, this may be an artifact of community-based recruitment strategies. For the field of psychology, the effects of this disjuncture are twofold: it provides privileged individuals (i.e., white, heterosexual) greater social latitude to define CNM relationships; and, it disregards the fluidity of definitions surrounding CNM relationships for individuals on the margins. Consequently, little is known regarding who is actually engaged in these relationships.

Motivated by a lack of research utilizing general recruitment strategies, this paper will provide a comparative analysis of descriptive statistics of individuals engaged in CNM and monogamous relationships as a framework to critically analyze gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age. Using data from two large online samples, we examined the extent to which individuals with certain demographic variables (gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age) are over- or under-represented in CNM and monogamous relationships. Moreover, we will provide frequencies (and means) for participants’ gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age.

Method

The current study utilizes data from two large online convenience studies (see Conley, Moors, Matsick, & Ziegler, 2012, Study 2; Moors, Conley & Edelstein, & Chopik, under review, Study 1). The first study, collected in spring 2010, investigated people’s perceptions of different types of relationships. The second study, collected in summer 2009, investigated personality characteristics and relationships.

Items that assessed relationship type and demographic characteristics from the Conley and colleagues study (N = 1,101) and the Moors and colleagues’ study (N = 1,775) were combined. Of the original 2,876 participants, 481 were excluded from final analysis because they either did not indicate their current relationship type (N = 268) or were not currently in a relationship (N = 213). Thus, the final data yielded 2,395 participants.

Recruitment Strategies

Participants for both studies were recruited online via two social networking sites: Craigslist.org (volunteer sections) and Facebook.com. Undergraduate research assistants used standardized language for posting surveys. Advertisements for recruitment in both studies solicited volunteers to participate in a study about «attitudes toward relationships,” and anyone over the age of 18 was encouraged to participate. Neither of the surveys’ postings targeted individuals engaged in CNM (nor any other population) to take part in this study. Additionally, we attempted to minimize selection bias by omitting that some of the surveys’ questions were related to CNM in the wording of the study advertisements.

Measures

Engagement in CNM and monogamy were assessed two different ways: an identity measure was used to assess relationship type in the Conley and colleagues (2012) study, and a behavioral measure was used to assess relationship type in the Moors and colleagues (under review) study. We purposely included a different assessment of relationship type in each study to examine if the frequency of people who identify as part of a CNM relationship would differ based on how the questions were asked. Moreover, for some participants, behavior (e.g., items such as «you and your partner take on a third partner to join you in your relationship on equal terms”) may better assess an individual’s engagement in CNM than self-identification with a specific type of CNM (e.g., «I am part of a polyamorous relationship”).

Identity measure. In the Conley and colleagues (2012) study, participants were first asked «Are you currently in a romantic relationship?” Those who selected «yes” were asked to identify which type of romantic relationship, options included: «monogamous (exclusively dating one person),” «casual dating (dating one or more people),” and «consensual non- monogamous relationship (dating one or more people and your romantic partners agree/know about it; for example, open relationship, polyamorous relationship, swinging relationship).” For the purpose of the present study, we removed individuals who were casually dating from the analyses because we are interested in comparisons between CNM and monogamous relationships.

Behavioral measure. Moors and colleagues (under review) used a newly created 6-item scale that assessed individuals’ willingness to engage in various CNM relationships (i.e., swinging, polyamory, and open relationships). Participants rated the extent to which they were willing to engage in each type of CNM arrangement, using a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very unwilling) to 7 (very willing), with an eighth option that specified «I'm currently in this type of relationship.” Sample items included: «You and your partner may have sex with others, but never the same person more than once,” «You and your partner may have sex with whomever they want, but there must be no secrets between you,” and «You and your partner take on a third partner to join you in your relationship on equal terms.” Participants who indicated current engagement in any of the behavioral assessments of CNM formed a CNM group. Additionally, participants were asked if they were currently in a monogamous relationship, with those indicating «yes” combined into a monogamous comparison group. Of importance, identity labels indicating a particular form of CNM were not included in any of the descriptions.

Results and Discussion

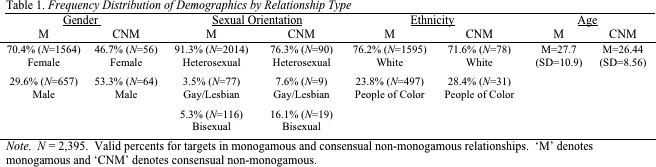

Of the 2,395 participants, 5.3% identified as part of a CNM relationship. The original two samples did not significantly differ in rates of CNM engagement; in other words, identity and behavioral assessments of CNM yielded similar rates of CNM engagement. Across both monogamous and CNM relationships, 69% of participants identified as female and 31% identified as male. In terms of sexual orientation, 90% identified as heterosexual, 4% as lesbian/gay, and 6% as bisexual. The sample was ethnically diverse, 76% identified as White, 8% African American, 9% Latino/a, 4% multiracial, and 3% Asian/Pacific Islander. Lastly, the ages of participants ranged from 18-84 years old (Mage = 27.7; SD = 10.79).[2] See Table 1 for frequencies, means, and standard deviations separated by type of relationship.

Participation in Monogamous and CNM Relationships: Considering Gender

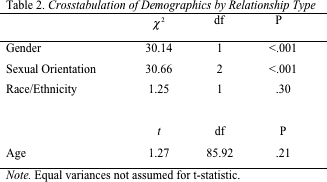

A chi-square goodness of fit test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between men and women’s likelihood to engage in monogamous or CNM relationships. Results indicate that there was no significant difference between observed and expected frequencies across gender and relationship type. That is, men and women were equally likely to take part in monogamous and CNM relationships. However, when looking within CNM relationships, more men were represented in CNM relationships than women,; see Table 2 for results.

On the surface level, these results appear to support an evolutionary psychology perspective which posits that men, in comparison to women, desire a greater number of sexual partners due to their unlimited supply of sperm and minimal paternal investment (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). According to this framework, men may view CNM as evolutionarily advantageous given that it potentially increases parental fitness with access to multiple partners. However, when taking into account restrictive views of women’s sexuality in United States culture, violations of sexuality-related prescriptions provide a more nuanced understanding of gender differences within CNM than evolutionary perspectives alone (see Conley, Moors, Matsick, Ziegler, & Valentine, 2011, for a review). Women are more stigmatized (relative to men) for participating in the same sexual behaviors—a social phenomenon known as the sexual double standard (see Crawford & Pop, 2003 for a review). Though women and men are not differentially judged for standard sexual behaviors (i.e., sex with few partners, premarital sex), the social repercussions of sexual double standards become more obvious when target individuals engage in less widely-accepted sexual practices (Conley, 2011; Conley, Ziegler, & Moors, 2012; Marks & Fraley, 2005). Perhaps, women were less likely to self-report that they were part of a CNM relationship because of social desirability to conform to norms surrounding sexuality.

Although our previous research investigating the sexual double standard has explored gender differences in casual sex (Conley, Ziegler, & Moors, 2012; Conley, Ziegler, Rubin, Kazemi, Moors, & Matsick, under review), women’s heightened awareness of differential stigmatization may also affect representation within CNM relationships. Whereas stigma plays a role in both men’s and women’s sexual decision-making processes, research shows that women may be more aware of the existence of sexual double standard than men (Sprecher, 1989; Sprecher, McKinney, Walsh & Anderson, 1989), and this recognition can influence women’s choices regarding participation in stigmatized sexual behaviors (Conley, Ziegler, & Moors, 2012). Potentially, greater recognition of sexual double standards may compel fewer women to be engaged in CNM relationships relative to men for fear of social opprobrium. Additional research should be conducted to investigate experiences and perceptions of gender-specific engagement in CNM in an effort to more fully understand participation in sexual and/or romantic relationships and behaviors that risk social disapproval (Moors, Matsick, Ziegler, Rubin & Conley, under review). Furthermore, research should assess if women perceive greater stigma than men for engaging in CNM, regardless of how they are actually viewed, as this may be a greater predictor of gender differences sex (Conley, Ziegler, & Moors, 2012; Conley et al., under review).

Participation in Monogamous and CNM Relationships: Considering Race/Ethnicity

A chi-square goodness of fit test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between individuals of color and White individuals’ likelihood to engage in monogamous or CNM relationships. We conceptualized any person who identified as non-White (e.g., African American/Black, Asian/Asian American, Latino/a, Native American, multiracial) as an individual of color. Results indicate that there was no significant difference between observed and expected frequencies across race and relationship type. That is, people of color and White individuals were equally likely to take part in monogamous and CNM relationships. Additionally, individuals of color and White individuals were also equally represented within monogamous and CNM relationships, respectively; see Table 2 for results.

Contrary to previous research findings (e.g., Sheff, 2005; Sheff & Hammers, 2011), individuals of color were equally as likely to engage in CNM as White individuals. Although these results emphasize greater racial/ethnic diversity in CNM than previously documented, the proportion of individuals of color who took part in either study was relatively low (28.4%). Regardless, the present results are the first to indicate that White individuals are not disproportionally represented in CNM relationships.

While previous research has found racial homogeneity among individuals engaged in CNM (Sheff & Hammers, 2011), this might be a by-product of community-based recruitment strategies that garner subjects from predominantly White social networks. Several barriers may dissuade people of color from participating in mainstream CNM communities, thereby contributing to monochromatic samples. A content analysis of consensual non-monogamous texts (i.e., «self help” style books and narratives) found that discourse often assumes an audience of White individuals, subsequently omitting the experiences of people of color (Nöel, 2006) and perpetuating essentialist perceptions of race and sexuality (Willey, 2006, 2010). This «culture of Whiteness” is often reproduced within mainstream CNM communities and events. In an ethnographic study of polyamorous individuals, Sheff (2005) found that some participants of color felt vulnerable at mostly-White events due to their race. Consequently, the reproduction of White privilege in both literature and mainstream community spaces might deter individuals of color from participating in popular CNM social networks.

It is probable that there are diverse practices and meanings of CNM for individuals of color, and this variety should be reflected in sampling techniques and recruitment strategies. Although results suggest that individuals of color are equally likely to engage in CNM relationships as White individuals, more nuanced research using different assessments of CNM are needed to elucidate this finding. Language that assesses CNM through both behavior and identity may broaden sample diversity, especially given that labels such as «polyamory” and «swinger” cater to a small subset of the population. Thus, expanding appraisals of CNM relationships is integral to the development of a more comprehensive understanding of these relationships within the wider population.

Participation in Monogamous and CNM Relationships: Considering Sexual Orientation

A chi-square goodness of fit test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between sexual minorities (i.e., lesbian, gay, and bisexual) and heterosexuals’ likelihood to engage in monogamous or CNM relationships.[3] Results indicate that there was no significant difference between observed and expected frequencies across sexual orientation and relationship type. That is, sexual minorities and heterosexuals were equally likely to take part in monogamous and CNM relationships. Although there were no differences between the proportion of sexual minorities in both types of relationships, results show that sexual minorities were more likely to be in CNM relationships than heterosexual individuals, ; see Table 2 for results.

Interestingly, previous research has suggested the primacy of the heterosexual dyad in CNM relationships (O’Neill & O’Neill, 1970; Constantine & Constantine, 1973; Smith & Smith, 1974; Jenks, 1998). Results of the present research, however, are similar to other findings that regard CNM as a component of sexual minority culture (although we would like to reiterate that there is no representative data regarding the frequency of CNM and monogamous relationships among sexual minorities and heterosexuals; Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; Solomon, Rothblum, & Baslom, 2005). Recent shifts in attitudes regarding monogamy and CNM among sexual minorities (regardless of gender) may elucidate this finding. Moors and colleagues (this issue) found that there were no differences between male and female sexual minorities’ desire to engage in sexual and romance types of consensual non-monogamy (polyamory) or sexual-oriented types of consensual non-monogamy (swinging). Thus, while monogamy may be a part of some sexual minority partnerships, positive attitudes towards CNM may contribute to greater rates of representation relative to heterosexuals.

Although past research has primarily focused on the fluidity of sexual orientation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals across the lifespan (Diamond, 2009), contextual factors may also contribute to changes in sexuality (e.g., Preciado & Peplau, 2011). Some authors emphasize the potential of CNM relationships to amend heteronormative standards regarding sexuality by allowing individuals to connect differently both romantically and sexually with men and women (Anderlini-D’Onofrio, 2004; Pallotta-Chiarolli, 1995; Ziegler, Matsick, Moors, Rubin & Conley, this issue). Thus, an overrepresentation of sexual minorities in CNM relationships may reflect the impact of social context on changes in sexual orientation.

While we know of no research that explores the causal effects of different relationship configurations (i.e., monogamous and CNM) on sexual identity, a recent experimental study by Preciado, Johnson, & Peplau (2013) found that social context directly influences changes in self-perceived sexual orientation among heterosexual men and women. Though sexual orientation is often approached as a unitary construct, it includes both actual sexual experiences of attraction, behavior, and fantasy and individual beliefs about those occurrences (i.e., self-perceived sexual orientation). Preciado and colleagues found that LGBQ-affirming situational cues led to participants reporting greater attraction to members of the same-sex than LGBQ-stigmatizing situational cues. That is, social context seems to influence how individuals interpret attitudes regarding same-sex experiences and beliefs and, in turn, their own desires and attractions. Although it is unclear if engagement in CNM is a stable identity, the underlying mechanism that changes people’s self-perception of sexual orientation may function similarly for individuals engaged in CNM. Subsequently, participation in CNM may change an individual’s perception of his/her sexual orientation.

Given that departures from monogamy are viewed as nontraditional, these relationships may allow individuals greater permissibility to explore same-sex attractions. Potentially, social cues, such as a supportive environment that encourages multiple romantic and/or sexual relationships may promote greater sexual self-expression by altering how individuals both approach and define sexuality. This, in turn, may lead to a departure from heterosexual identification. Future research should investigate the role of situational cues within CNM relationships and their potential effects on sexual orientation.

Participation in Monogamous and CNM Relationships: Considering Age

We conducted a t-test to determine if there were age differences among individuals in monogamous and CNM relationships. Results show that there was no age difference between individuals in monogamous (M = 27.79) or CNM relationships (M = 26.44), t(85.92) = 1.27, p = 0.21. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 0.6.22 p = 0.013), with the degrees of freedom adjusted from 1234 to 85.92; see Table 2 for results. Additionally, our sample provided a large age range (18 to 84 years old) across both samples.

Previous research on CNM reveals a relatively older population, with participants ranging in age from their late 20’s to early 50’s (Sheff, 2005; Jenks, 1985; Levitt, 1988). Similar to past studies that found racial homogeneity among individuals engaged in CNM, skewed age demographics might be an artifact of community-based recruitment strategies that collect data from predominantly older social networks. Researchers, then, should be mindful of selection bias regarding age as well as take into account both the relational trajectory and individual cycles of sexual and/or romantic partnerships across the life course. In other words, we suggest that either CNM or monogamous relationships may be more efficacious at various points in people’s lives.

Although we know of no research that has addressed rates of engagement in CNM and monogamy across the lifespan, the dynamic nature of relationships may further explain the proclivity for certain configurations. For example, the conventional relationship course of young adulthood appears to be serial monogamy, in which individuals partake in a series of brief monogamous relationships. Monogamy may be seen as an effective strategy for establishing a long-term romantic partnership early in one’s relational trajectory (Conley, Moors, Matsick, & Ziegler, 2012). Conversely, increased popularity of sexual permissiveness among young adults (i.e., «hooking up”; Armstrong, England, & Fogarty, 2010) may signal a generational shift in preference for concurrent sexual partnerships. As individuals transition to later adulthood, both CNM and monogamy may also be advantageous relationship choices. For instance, given that marriage is seen as normative and an expected milestone within the United States (DePaulo & Morris, 2005), older adults may engage in monogamous partnerships because of these sociocultural expectations. However, once a long-term partnership has been established, a relationship may become routine and monotonous and, thus, CNM may become a potential avenue to maintain a primary partnership while simultaneously engaging in additional sexual and/or romantic experiences. As a result, we believe that investigating age in conjunction with the stability of one’s relationship type preference would provide a critical new direction for future CNM and identity-based research.

Productive Future Directions

The purpose of the current research was twofold—to highlight the identities of individuals engaged in CNM relationships and to promote future CNM research that is more inclusive of diverse identities and behaviors that are outside the margins of traditional relationship frameworks. For this reason, our research uses both behavioral and identity-based measures of CNM engagement in order to acquire a sample of individuals who may differ in experiences, identities, and relationship type, but who all participate in relationships that depart from a monogamous agreement. This coupling of measures affords researchers with a more diverse sample of participants who engage in CNM; thus, future researchers interested in the prevalence of CNM should be mindful of this approach.

Further, we encourage researchers to seek out nationally representative samples—as opposed to those acquired through snowball sampling techniques—in order to assess the prevalence of CNM. Relatedly, we acknowledge critiques of Internet recruitment strategies (e.g., Azar, 2000; Birnbaum, 2004); however, research indicates that web-based survey research is still highly worthwhile. For instance, Internet-based data collection yields sample representativeness (Chang & Krosnick, 2002) perhaps more so then university subject pools which are generally younger and less diverse than the larger population (Stevenson, 2012). This is particularly important in sexuality research, in which homogenous samples may restrict the generalizability of results based on various demographics (e.g., sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, age). Of note, we did not have measures to assess socioeconomic status and level of education in the current research (nor did we have sample sizes large enough to conduct analyses for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals separately). The inclusion of these demographic variables would strengthen future research designs that target people in CNM relationships.

Lastly, based on our results presented in Table 2, we advise scholars to use recruitment strategies that could garner more individuals of color who engage in CNM relationships. The results of the current research suggest that engagement in CNM relationships is not limited to a racially homogenous population, with people of color participating in a variety of alternative sexual and/or romantic relationship configurations. We do not suggest that people of color are protected against the discriminatory impacts of sexual stigma similar to those with racial and/or class privileges. That is, people of color must navigate the sociohistorical positioning of non-White sexualities as deviant and excessive (Collins, 2005; hooks, 1981), and this unsettling reality may impact public declarations of unconventional sexual practices (Sheff & Hammers, 2011). As a result, people of color who engage in CNM may not have the social visibility as White individuals in CNM relationships and communities; therefore, we believe it is especially important to elucidate the racial/ethnic diversity of those engaged in CNM via recruitment strategies to create a more accurate picture of «the face” of CNM relationships.

References

Anapol, D. (2010). Polyamory in the 21st century: Love and intimacy with multiple partners.

Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Anderlini-D’Onofrio S (2004) Plural Loves: Designs for Bi and Poly Living. Binghamton, NY:

Harrington Park Press.

Aral, S. O., & Leichliter, J. S. (2010). Non-monogamy: risk factor for STI transmission and

acquisition and determinant of STI spread in populations. Sexually transmitted infections,

86(Suppl 3), iii29-iii36.

Armstrong, E. A., England, P., & Fogarty, A. C. (2012). Accounting for Women’s Orgasm and Sexual Enjoyment in College Hookups and Relationships. American Sociological Review, 77(3), 435-462.

Azar, B. (2000). A web of research: They’re fun, they’re fast, and they save money, but do Web experiments yield quality results? Monitor on Psychology, 31, 42–47.

Barker, M. (2005a). On tops, bottoms and ethical sluts: The place of BDSM and polyamory in lesbian and gay psychology. Lesbian & Gay Psychology Review, 6(2), 124–129.

Barker M (2005b) This is my partner and this is my...partner’s partner: Constructing a polyamorous identity in a monogamous world. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 18(1): 75–88.

Barker, M., & Langdridge, D. (2010). Understanding non-monogamies. New York: Routledge.

Bennett, J. (2009, July 29). Only You. And You. And You. Newsweek. Retrieved from www.newsweek.com/2009/07/28/only-you-and-you-and-you.html.

Bettinger, M. (2005). Polyamory and gay men: A family systems approach. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 1(1), 97.

Birnbaum, M. H. (2004). Human research and data collection via the Internet. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 803-832.

Blumstein P and Schwartz P (1983) American Couples: Money-Work-Sex. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Bonello, K., & Cross, M. C. (2010). Gay monogamy: I love you but I can’t have sex with only you. Journal of Homosexuality, 57, 117-139.

Bryant, A. S., & Demian. (1994). Relationship characteristics of American gay and lesbian couples: Findings from a national survey. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 1(2), 101-117.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232.

Campbell, K. (2000). Relationship characteristics, social support, masculine ideologies and psychological functioning of gay men in couples. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. California School of Professional Psychology. Alameda, CA.

Chang, L., & Krosnick, J. (2002). A comparison of the random digit dialing telephone survey methodology with Internet survey methodology as implemented by Knowledge Networks and Harris Interactive. American Political Science Association.

Cole, C. L., & Spaniard, G. B. (1974). Comarital mate‐sharing and family stability. Journal of Sex Research, 10(1), 21-31.

Collins, P. (2005). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Conley, T. D. (2011). Perceived proposer personality characteristics and gender differences in acceptance of casual sex offers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 309– 329.

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2011). Prevalence of consensual non- monogamy in general samples. Unpublished data.

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., & Moors, A. C. (2012). Backlash From the Bedroom Stigma Mediates Gender Differences in Acceptance of Casual Sex Offers. Psychology of Women Quarterly.

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2012). The Fewer the Merrier?: Assessing Stigma Surrounding Consensually Non‐monogamous Romantic Relationships. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy.

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Valentine, B. (2012). A Critical Examination of Popular Assumptions About the Benefits and Outcomes of Monogamous Relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 17(2), 124-141.

Conley, T.D., Ziegler, A., Rubin, J., Kazemi, J., Moors, A.C., & Matsick, J.L. (under review). Closing the Gender Gap in Casual Sex: The Mediational Role of Stigma and Pleasure.

Constantine, L. L., & Constantine, J. M. (1973). Group marriage: A study of contemporary multilateral marriage. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 13–26.

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inquiry, 16(2-3), 57-83.

Diamond, L. M. (2009). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women's love and desire. Harvard University Press.

Finn, M. and Malson, H. (2008). Speaking of home truth: (Re)productions of dyadic commitment in non-monogamous relationships. British Journal of Social Psychology 47(3):519–533.

Frank K and DeLamater J (2010) Deconstructing monogamy: Boundaries, identities, and fluidities across relationships. In: Barker M and Langdridge D (eds) Understanding Non- Monogamies. New York: Routledge, 9–22.

Haritaworn, J., Lin, C. J., & Klesse, C. (2006). Poly/logue: A critical introduction to polyamory. Sexualities, London, 9(5), 515.

Hooks, B. (1981). Ain't I a woman: Black women and feminism (Vol. 3). Boston: South End Press.

Hyde, J. S., & DeLamater, J. D. (2000). Understanding human sexuality (7th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Jenks, R. (1985). Swinging: A replication and test of a theory. Journal of Sex Research 21, 199- 205.

Jenks, R. J. (1998). Swinging: A review of the literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27(5), 507-521.

Klesse C (2005) Bisexual women, non-monogamy and differentialist anti-promiscuity dis-

courses. Sexualities 8(4): 445–464.

Klesse C (2006) Polyamory and its ‘others’: Contesting the terms of non-monogamy. Sexualities 9(5), 565–583.

Klesse, C. (2007). The specter of promiscuity: Gay male and bisexual non-monogamies and polyamories. London: Ashgate Publishers.

LaSala, M. C. (2005). Extradyadic sex and gay male couples: Comparing monogamous and nonmonogamous relationships. Families in Society, 85(3), 405-412.

Levitt E. E. (1988). Alternative life style and marital satisfaction: A brief report. Journal of Sexual Abuse,1(3), 455-461.

Marks, M. J., & Fraley, R. C. (2005). The sexual double standard: Fact or fiction?. Sex Roles, 52(3-4), 175-186.

Moors, A. C., Conley, T. D., Edelstein, R. S., & Chopik, W. J. (under review). Attached to monogamy? Avoidance predicts willingness to engage (but not actual engagement) in consensual non-monogamy.

Moors, A.C., Rubin, J.D., Matsick, J.L., Ziegler, A. & Conley, T.D. (this issue). It’s just not a gay male thing: Sexual minority men and women are equally attracted to consensual non-monogamy.

Moors, A.C., Matsick, J.L, Ziegler, A., Rubin, J.D., Conley, T. (under review). Stigma toward Individuals Engaged in Consensual Non-Monogamy: Robust and Worthy of Additional Research

Nöel, MJ (2006) Progressive polyamory: Considering issues of diversity. Sexualities 9(5): 602–620.

O’Neill, G., & O’Neill, N. (1970). Patterns in group sexual activity. The Journal of Sex Research, 6(2), 101-112.

O’Neill, N., & O’Neill, G. (1972a). Open marriage: A new life style for couples. New York, NY: M. Evans.

Pallotta-Chiarolli M (1995) Choosing not to choose: Beyond monogamy, beyond duality. In: Lano K and Parry C (eds) Breaking the Barriers of Desire. Nottingham: Five Leaves Publication, 41–67.

Preciado, M. A., & Peplau, L. A. (2011). Self-perception of same-sex sexuality among heterosexual women: Association with personal need for structure. Self & Identity, 11, 137–147.

Preciado, M. A., Johnson, K. L., & Peplau, L. A. (2013). The Impact of Cues of Stigma and Support on Self-Perceived Sexual Orientation among Heterosexually Identified Men and Women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Ravenscroft, T (2004) Polyamory: Roadmaps for the Clueless and Hopeful. Santa Fe, NM: Crossquarter Publishing Group.

Ritchie, A., & Barker, M. (2006). ‘There Aren’t Words for What We Do or How We Feel So We Have To Make Them Up’: Constructing Polyamorous Languages in a Culture of Compulsory Monogamy. Sexualities, 9(5), 584-601.

Rohter, L. (2010, March 26). Sweaty Equity, the Movie, NY Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/28/movies/28breaking.html?ref=movies.

Rothblum, E. D. (2009). An overview of same-sex couples in relation ships: A research area still at sea. In Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (pp. 113- 139). Springer New York.

Rust P (1996) Monogamy and polyamory: Relationship issues for bisexuals. In: Beth F (ed.) Bisexuality: The Psychology and Politics of an Invisible Minority. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 127–148.

Sheff, E. (2005). Polyamorous women, sexual subjectivity, and power. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 34(3), 251–283.

Sheff, E. & Hammers, C. (2011). The privilege of perversities: race, class and education among polyamorists and kinksters. Psychology & Sexuality, 2:3, 198-22.

Shernoff M (2006) Negotiated non-monogamy and male couples. Family Process 45(4): 407– 418.

Smith, J. R., & Smith, L. G. (1974). Co-marital sex and the sexual freedom movement. In J. R. Smith & L. G. Smith (Eds.), Beyond monogamy: Recent studies of sexual alternatives in marriage (pp. 202-213). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Solomon, S. E., Rothblum, E. D., & Balsam, K. F. (2005). Money, housework, sex, and conflict: Same-sex couples in civil unions, those not in civil unions, and heterosexual married siblings. Sex Roles, 52, 561–575.

Sprecher, S. (1989). The importance to males and females of physical attractiveness, earning potential and expressiveness in initial attraction. Sex Roles, 21, 591–607.

Sprecher, S., McKinney, K., Walsh, R., & Anderson, C. (1988). A revision of the Reiss premarital sexual permissiveness scale. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50, 821–828.

Stevenson, M. (2012) Conceptualizing Diversity in Sexuality Research. In M.W. Wiederman and B. E. Whitley (Eds.) Handbook for Conducting Research on Human Sexuality. Mahwah, MD: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Taormino, T. (2008). Opening up: A guide to creating and sustaining open relationships. San Francisco: Cleis Press.

Sklar, H. L. (2010, March). Meet the swingers. SELF.

Valentine, B., & Conley, T.D. (under review). Testing the Benefits of Monogamy: Gay Men and Consensually Non-Monogamous Relationships

Wilkinson E (2010) What’s queer about non-monogamy now? In: Barker M and Langdridge D. (eds) Understanding Non-Monogamies. New York: Routledge, 243–254.

Willey A (2006). ‘Christian nations’, ‘polygamic races’ and women’s rights: Toward a genealogy of non/monogamy and whiteness. Sexualities 9(5): 530–546.

Willey A (2010) ‘Science says she’s gotta have it’: Reading for racial resonances in woman- centred poly literature. In: Barker M and Langdridge D (eds) Understanding Non Monogamies. New York: Routledge, 34–45.

Ziegler, A., Matsick, J.L., Moors, A.C., Rubin, J.D., & Conley, T.D. (this issue). Does Polyamory Harm Women?: Deconstructing Polyamory with a Gendered Lens.