It’s Not Just a Gay Male Thing: Sexual Minority Women and Men are Equally Attracted to Consensual Non-monogamy

Summary

Concerned with the invisibility of non-gay male interests in alternatives to monogamy, the present study empirically examines three questions: Are there differences between female and male sexual minorities in a) attitudes toward consensual non-monogamy, and b) desire to engage in different types of consensual non-monogamy (e.g., sexual and romantic/polyamory versus sexual only/swinging), and c) schemas for love? An online community sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals (n = 111) were recruited for a study about attitudes toward relationships. Results show that sexual minority men and women hold similar attitudes toward CNM and similar levels of desire to engage in these types of relationships. Additionally, there were no differences between male and female sexual minorities’ desire to engage in sexual and romantic types of consensual non-monogamy (polyamory) or sexual-oriented types of consensual non-monogamy (swinging). There were also no differences in preference for specific types of love styles among LGB individuals. In sum, it is not just gay men who express interest in these types of relationships.

Keywords: consensual non-monogamy, polyamory, swinging, love styles, LGB individuals

»You'll also see that all gay men in successful, healthy, loving, long-term relationships monogamous or not—place a high value loyalty, trust, commitment, and, yes, self-control. (Being in an open relationship does not mean accepting every offer of sex!) And you'll see that there's nothing "superficial" about non-monogamous relationships« (Savage, 2012).

In a recent edition of Savage Love, a popular sex advice column written by Dan Savage, an anonymous gay male reader critiqued Savage’s (presumed) stance on consensual non-monogamy (CNM; a relationship in which partners agree to have extradydadic romantic and/or sexual partners) through a disparaging response. The anonymous reader claims that such relationships should not be tolerated in the gay community. Additionally, given Savage’s fame, the reader warns that Savage should be cautious about his writings concerning sexual minority relationships because of the high amount of promiscuity in the gay community. As illustrated in Savage’s response to the reader above, he emphasizes that both monogamous and non-monogamous relationships can be successful. Perhaps most importantly, he accentuates that engaging in CNM does not equate to sex with anyone who offers, thus dispelling common stereotypes about promiscuity within gay male relationships.

In line with the reader seeking advice from Savage, research has shown that people perceive gay men as sexually risky and their relationships as low in quality and satisfaction (Moors, Matsick, Ziegler, Rubin, & Conley, 2013; Peplau, 1993). However, when these stereotypes have been studied for accuracy, empirical evidence does not support these myths (see Peplau, 1993; Peplau & Spalding, 2003; for reviews). As outlined by Peplau and colleagues, gay men (and lesbians and bisexuals) are engaged in committed, satisfying, and functional romantic relationships and also have supportive social networks.

Perceptions of Consensual Non-monogamy

Similar to stereotypes surrounding gay male relationships, CNM relationships are stigmatized and a halo effect surrounds monogamous relationships (Conley, Moors, Matsick, & Ziegler, 2013; Matsick, Conley Ziegler, Moors, & Rubin, 2013; Moors, et al., 2013). Specifically, CNM relationships (and the individuals in them) are perceived as sexually riskier, lower in relationship quality, less sexually satisfying, lonelier, and less socially acceptable than monogamous relationships (Conley, Moors, Matsick, et al., 2013). When taking into account participants’ sexual orientation, both heterosexuals and sexual minority individuals overwhelmingly viewed monogamy as more positive than CNM (Conley, Moors, Matsick, et al., 2013). This stigmatization extends to those in CNM relationships regardless of a target’s sexual orientation, gender, or happiness with their current relationship arrangement (Moors, et al., 2013).

Research suggests that approximately 4-5% of individuals (regardless of sexual orientation or gender) are involved in some type of CNM relationship (i.e., swinging, polyamory, open relationship; Conley, Moors, Matsick, & Ziegler, 2011; J. D. Rubin, Moors, Matsick, Ziegler, & Conley, this issue). Although frequency of gay males’ involvement in CNM is unclear, some research (albeit, small non-representative samples) shows approximately 20% of gay men in relationships mutually agree to engage in extradyadic sex, with other estimates as high as 56% (Campbell, 2000; Hickson et al., 1992; LaSala, 2005).

Parallel to myths about sexual minorities and romantic relationships, there is little evidence to support the negative perceptions that surround CNM relationships (see Conley, Ziegler, Moors, Matsick, & Valentine, 2012; for a review). For example, compared to sexually unfaithful individuals (those who have cheated in a monogamous relationship), individuals in CNM relationships were more likely to engage in a variety of safer sexual behaviors, including greater likelihood of correct condom use (Conley, Moors, Ziegler, Matsick, & Rubin, 2013; Conley, et al., 2012). Similarly, research shows that, compared to individuals in monogamous relationships, individuals in CNM relationships are equally satisfied with and committed to their relationships as well as experience less jealousy (see Conley, et al., 2012; for a review). In terms of gay men in CNM relationships, research has documented that they are equal (sometimes higher) in satisfaction, closeness, love, and relationship longevity in comparison to gay men in monogamous relationships (Blasband & Peplau, 1985; Kurdek, 1988).

Taken together, people’s stereotypes about gay men and CNM relationships are that these relationships leave individuals unsatisfied. In the present research, we examined the accuracy of stereotypes surrounding sexual minorities’ attitudes toward CNM and desire to engage in these relationships. In the next section, we consider sexual minorities’ approaches to relationships through schemas for love.

Schemas for Love

Attitudes and beliefs regarding love can differentially impact sexual and relational dynamics for both men and women (Fricker & Moore, 2002). While social and behavioral scientists have proposed a number of taxonomies for the classification of love, Lee’s (1977) framework provides a multidimensional approach to examining love using six different styles: Eros (passionate love), Ludus (game-playing love), Storge (friendship love), Mania (obsessive love), Pragma (practical love), and Agape (altruistic love). These »styles of loving« can be conceptualized as schemas for how people think about, desire, and navigate romantic relationships.

There are consistent gender differences between heterosexual men and women for most love styles. For instance, women endorse Storge, Pragma, and Mania love styles more strongly than men, whereas, men tend to be higher in Ludus (see S. S. Hendrick, 1995; for a brief review). In other words, women tend to navigate love using friendship and practical approaches but are also prone to possessiveness or jealousy. In contrast, men’s approaches to love often involve game playing tactics and avoidance of intimacy and commitment.

There is little research on love styles among sexual minorities and most focuses on the experiences of gay men. In a comparison study between heterosexual and gay men, the two groups showed similarities in love styles (Adler, Hendrick, & Hendrick, 1986). Specifically, the two groups only differed significantly on approaches to Agapic love. This effect, however, was driven by regional differences within the sample (Adler, et al., 1986). Thus, similar to heterosexual men in previous studies, gay men should have higher scores on Ludus and lower scores on Storge and Mania.

Although assessing love through Lee’s model has fallen out of vogue among psychologists, we see utility in love styles and conceptualization of these as measures of global attitudes toward love. That is, Lee’s multidimensional approach to examining love considers six unique dispositions that people use to navigate relationships and to define what they prefer in partners. Moreover, there are documented differences between heterosexual men and women; however, substantially less is known about how these styles relate to sexual minorities. Thus, the present paper examines male and female sexual minorities’ schemas for love.

Present Study

Research suggests that gay men are more inclined to favor and participate in CNM (LaSala, 2005); however, it is unknown if other sexual minorities favor these types of relationships to the same extent. Researchers may have assumed that gay men are the only members of the LGB community inclined to engage in CNM; however, bisexual men and women as well as lesbian women may also be attracted to these relationships. Motivated by the lack of research examining differences within sexual minorities and their proclivity to engage in CNM, we sought to address whether sexual minority men have more positive attitudes toward different types of CNM than sexual minority women. We examined three questions: Are there differences between female and male sexual minorities in a) attitudes toward CNM, b) desire to engage in different types of CNM relationships (e.g., sexual only v. sexual and romantic), and c) preferences for specific types of love, especially those that are associated with greater non-monogamy?

Specifically, we examined attitudes toward and willingness to engage in different types of CNM, including sexual only CNM (swinging) and sexual and romantic CNM relationships (polyamory) among sexual minority men and women. We also utilized an existing validated scale addressing attitudes toward different love styles. This scale was purposefully chosen because the different love styles vary in the extent to which they reflect ideals associated with traditional monogamous and more alternative CNM relationships.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited online via social networking sites (e.g., Craigslist.org and Facebook.com) to take part in a larger study about attitudes toward romantic relationships. In order to minimize selection bias, we did not indicate that some of the questions were about CNM nor did we specifically recruit for LGB individuals. Given the purpose of the present study and our recruitment strategies, we excluded a large number of participants. We excluded 1,667 participants who either identified as heterosexual or did not respond to the main variables of interest. The final sample included 110 sexual minorities; of these, 66% were female (identified as bisexual or lesbian) and 34% were male (identified as bisexual or gay). In terms of ethnic composition, our sample was 69% White, 13% African American, 10% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5% Latino/a, and 1% multiracial; the remaining did report ethnicity. The ages of participants ranged from 18-32 years old (Mage = 21.71; SD = 3.12).

Measures

We assessed attitudes toward CNM and willingness to engage in CNM through two newly-developed scales (Moors, Conley, Edelstein, & Chopik, 2014). Sample items from the six-item attitudes toward CNM scale (α = .90) include: »Every couple should be monogamous (reverse scored),« and »If people want to be in openly/consensually non-monogamous relationship, they have every right to do so.« Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each statement, using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items from the willingness to engage in CNM scale (α = .89) include: »You and your partner go together to swinger parties where partners are exchanged for the night,« and »You and your partner take on a third partner to join you in your relationship on equal terms.« Participants rated the extent to which they were willing to engage in each type of behavior using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unwilling) to 7 (very willing).

In order to assess love styles, we used the short version of the Love Attitudes Scale (C. Hendrick, Hendrick, & Dicke, 1998), including Eros (passionate love, α = .52), Ludus (game-playing love, α = .60), Storge (friendship love, α = .89), Pragma (practical love, α = .42), Mania (obsessive love, α = .70), and Agape (altruistic love, α = .78). Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each type of love style, using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Results

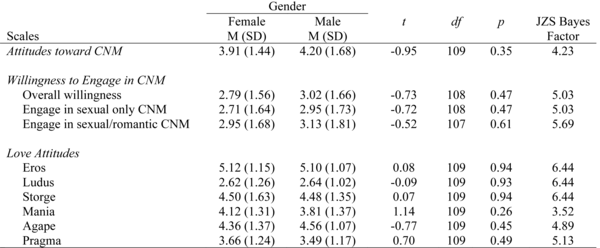

We conducted a total of ten t-tests, to examine if there are differences among female and male sexual minorities on attitudes toward CNM, desire to engage in different types of CNM relationships, and love styles. Given the large number of independent analyses (ten total), we used a Bonferroni correction and the critical alpha level was set at 0.05/10 or 0.005. Thus, for the tests to be statistically significant, the p-value had to be less than 0.005. Additionally, we used the Jeffrey-Zellner-Siow prior (JZS) Bayes factor for the largest non-significant difference for all null results to indicate the likelihood of accepting the null hypothesis over the alternative hypothesis (Rouder, Speckman, Sun, Morey, & Iverson, 2009).

Do Female and Male Sexual Minorities Differ on Attitudes toward CNM?

Endorsement of CNM did not significantly differ between female and male sexual minorities, t(109) = -0.95, p = 0.35; see Table 1 for means, standard deviations, and JZS Bayes factors. The JZA Bayes factor indicated the null to be 4.23 times as likely as the alternative. Previous research suggests that gay men may hold the highest positive regard toward CNM relationships; however, these findings illustrate that regardless of gender, sexual minorities hold equally positive attitudes toward CNM.

Table 1. Female and Male Sexual Minorities’ Scores on Love Styles, Attitudes toward CNM, and Willingness to Engage in CNM

Do Female and Male Sexual Minorities Differ on Willingness to Engage in CNM?

Similar to endorsement of attitudes toward CNM, willingness to engage in a variety of CNM relationships did not significantly differ among female and male sexual minorities, t(108) = -0.73, p = 0.47. The JZA Bayes factor indicated the null to be 5.03 times as likely as the alternative. In addition, we conducted two separate t-tests to determine if female and male sexual minorities’ desire to engage in CNM differs based on the type of CNM relationship in question. Specifically, we analyzed desires to engage in sexual-only CNM relationships (i.e., extradyadic sexual relations only, such as swinging) and sexual and romantic CNM relationships (i.e., relationships that may include both a sexual and romantic connection between partners, such as polyamory), separately. To examine sexual only CNM, we created a composite score of the three willingness items that were related to solely extradyadic sexual relationships (e.g., »You and your partner go together to swinger parties where partners are exchanged for the night«). Accordingly, we created a composite score of the three willingness items that described both sexual and romantic CNM relationships (e.g., »You and your partner take on a third partner to join you in your relationship on equal terms«). Both desire to engage in sexual-only CNM and sexual and romantic CNM did not significantly differ among female and male sexual minorities, t(108) = -0.72, p = 0.47 and t(107) = -0.52, p = 0.61, respectively. The JZS Bayes factors indicated the null to be 5.03 and 5.69 times as likely as the alternative, respectively. Across all analyses, there were no significant differences between desire to engage in either type of CNM for sexual minority women and men; see Table 1 for means, standard deviations, and JZS Bayes factors.

Do Female and Male Sexual Minorities Differ on Love Styles?

There were no significant differences between female and male sexual minorities on each of the six love styles, ts(109) = 0.08 - 1.14, all ps > .26; see Table 1 for means, standard deviations, and JZS Bayes factors. The range of JZS Bayes factors indicated the null to be 3.52 to 6.44 times as likely as the alternative(s). That is, female and male sexual minorities have similar styles of passionate love, game-playing love, friendship love, practical love, obsessive love, and altruistic love. These results do not support the stereotype that women endorse higher Pragma, Storge, and Mania love as well as lower Ludus love in comparison to men within a sexual minority sample.

Discussion

From a cursory glance of the literature on non-monogamies, one could easily assume that gay men desire CNM relationships more than other sexual minorities. There is a substantial body of literature that addresses gay men in CNM relationships (Bettinger, 2004; Blasband & Peplau, 1985; Bonello & Cross, 2010; Hickson, et al., 1992; Kurdek & Schmitt, 1986; LaSala, 2004, 2005). In contrast, a much smaller body of literature examines other sexual minorities’ (in particular bisexual women’s) engagement in multiple partnered relationships (Barker, 2005; Dixon, 1985; Ritchie & Barker, 2007) and lesbians’ non-monogamous relationships appear to be almost entirely absent from academic literature (with the exception of Stevens, 1993). From this, we can infer the consensus is that sexual minority men privilege CNM relationships and, perhaps relationships that are thought to engender non-monogamy (such as game-playing love and cheating relationships).

Although it may appear that gay men are the face of CNM among sexual minorities, the present study shows female and male sexual minorities hold similar attitudes toward CNM and similar levels of desire to engage in these types of relationships, illustrating that it is not just gay men who have interest in these types of relationships. In sum, there were no differences between female and male sexual minorities’ desire to engage in sexual-only types of CNM (swinging) or sexual and romantic types of CNM (polyamory). Additionally, we found no differences in love styles among female and male sexual minorities.

We suggest that future researchers consider the diversity of those interested in CNM rather that relegating the research to an association with a particular sexual minority identity. Indeed, sexuality research must navigate its own internal stereotypes and inequalities in regards to the study of human behavior (G. Rubin, 1999). However, it is from such conventional assumptions that hierarchies of gender, sexual orientation, and relationship preferences are reproduced in empirical research (Foucault, 1978). Thus, researchers should be value-neutral (Tiefer, 1987) in an effort to more fully understand the range of relationship choices among sexual minorities.

References

Adler, N. L., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1986). Male sexual preference and attitudes toward love and sexuality. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy, 12(2), 27-30.

Barker, M. (2005). This is my partner, and this is my… partner’s partner: Constructing a polyamorous identity in a monogamous world. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 18, 75-88.

Bettinger, M. (2004). Polyamory and gay men. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 1(1), 97-116.

Blasband, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1985). Sexual exclusivity versus openness in gay male couples. Archives of sexual behavior, 14(5), 395-412.

Bonello, K., & Cross, M. C. (2010). Gay monogamy: I love you but I can't have sex with only you. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(1), 117-139.

Campbell, K. (2000). Relationship characteristics, social support, masculine ideologies and psychological functioning of gay men in couples. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. California School of Professional Psychology. Alameda, CA. Retrieved from www.drkevincampbell.net/DissertationKevinMCampbell.pdf

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2011). Prevalence of consensual non-monogamy in general samples. Unpublished data.

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2013). The fewer the merrier: Assessing stigma surrounding non-normative romantic relationships Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 1-30.

Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Ziegler, A., Matsick, J. L., & Rubin, J. D. (2013). Condom use errors among sexually unfaithful and consensually nonmonogamous individuals. Sexual Health, 10(5), 463-464.

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Valentine, B. (2012). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 124-141.

Dixon, J. K. (1985). Sexuality and relationship changes in married females following the commencement of bisexual activity. Journal of Homosexuality, 11(1-2), 115-134.

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality. Vol. 1. New York: Vintage, 1980. Power/Knowledge.

Fricker, J., & Moore, S. (2002). Relationship satisfaction: The role of love styles and attachment styles. Current Research in Social Psychology, 7(11), 182-204.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S., & Dicke, A. (1998). The love attitudes scale: Short form. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(2), 147-159.

Hendrick, S. S. (1995). Close Relationships Research Applications to Counseling Psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 23(4), 649-665.

Hickson, F., Davies, P., Hunt, A., Weatherburn, P., McManus, T., & Coxon, A. (1992). Maintenance of open gay relationships: Some strategies for protection against HIV. Aids Care, 4(4), 409-419.

Kurdek, L. A. (1988). Relationship quality of gay and lesbian cohabiting couples. Journal of Homosexuality, 15, 93-118.

Kurdek, L. A., & Schmitt, J. P. (1986). Relationship quality of gay men in closed or open relationships. Journal of Homosexuality, 12, 364-369.

LaSala, M. C. (2004). Monogamy of the heart: Extradyadic sex and gay male couples. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 17, 3.

LaSala, M. C. (2005). Extradyadic sex and gay male couples: Comparing monogamous and nonmonogamous relationships. Families in Society, 85(3), 405-412.

Lee, J. A. (1977). A typology of styles of loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 173-182.

Matsick, J. L., Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., & Rubin, J. D. (2013). Love and sex: Polyamorous relationships are perceived more favourably than swinging and open relationships. Psychology & Sexuality, Advanced online publication: doi 10.1080/19419899.19412013.

Moors, A. C., Conley, T. D., Edelstein, R. S., & Chopik, W. J. (2014). Attached to monogamy?: Avoidance predicts willingness to engage (but not actual engagement) in consensual non-monogamy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, Advance online publication, doi: 10.1177/0265407514529065.

Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., Rubin, J., & Conley, T. D. (2013). Stigma toward individuals engaged in consensual non-monogamy: Robust and worthy of additional research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 52-69.

Peplau, L. A. (1993). Lesbian and gay relationships. In L. D. Garnets & D. C. Kimmel (Eds.), Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Male Experiences. New York Chichester: Columbia University Press.

Peplau, L. A., & Spalding, L. R. (2003). The close relationships of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. In L. Garnets & D. C. Kimmel (Eds.), Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Experiences (2 ed., pp. 449-474). New York: Columbia University Press.

Ritchie, A., & Barker, M. (2007). Hot bi babes and feminist families: Polyamorous women speak out. Lesbian and Gay Psychology Review, 8(2), 141-151.

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D., & Iverson, G. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(2), 225-237.

Rubin, G. (1999). Thinking sex: Notes for a radical theory of the politics of sexuality. In R. Parker & P. Aggleton (Eds.), Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader (pp. 143-179). London: UCL Press.

Rubin, J. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., & Conley, T. D. (this issue). On the margins: Considering diversity among consensually non-monogamous relationships. Journal fur Psychologie.

Savage, D. (2012, June 13). SL letter of the day: Do monogamous gay couples exist?, Savage Love. Retrieved from http://slog.thestranger.com/slog/archives/2012/06/20/sl-letter-of-the-day-do-monogamous-gay-couples-exist

Stevens, P. E. (1993). HIV risk reduction for three subgroups of lesbian and bisexual women in San Francisco -- Year one: Project evaluation report. San Francisco: Department of Public Health.

Tiefer, L. (1987). Social constructionism and the study of human sexuality. In P. Shaver & C. Hendrick (Eds.), Sex and Gender (pp. 70-94). NewburyPark: Sage Publications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their research assistants in the Stigmatized Sexualities Laboratory at the University of Michigan for all of their hard work and, in particular, Kelly Grahl.