Competences of teachers and other educational professionals as condition for the success of inclusive vocational guidance in general and vocational schools, exemplified on organizing work placements for students

Silvia Greiten, Thomas Bienengräber, Thomas Retzmann, Lütfiye Turhan & Marie Schröder

Journal für Psychologie, 27(2), 313b–333b

https://doi.org/10.30820/0942-2285-2019-2-313bwww.journal-fuer-psychologie.deSummary

Work placements for students bridge the gap between school and the world of work and the vocational training system. They are part of a comprehensive set of measures for vocational orientation and are organized by a multi-professional team of different actors, such as teachers and other educational staff involved in the process of secondary education and professionals working in institutions that accompany the transition. Though little research has been done on inclusive vocational guidance, it can be assumed that the complexity of this process will increase with new cooperations. This article presents results from multi-professional group discussions with participants from various institutions and derives competences for inclusive vocational guidance in schools. The results point to the necessity of identifying fields of action, investigating cooperation between actors within the school system and, above all, determining knowledge references that arise subject-specifically for inclusive vocational orientation from the needs of students with special educational needs.

Keywords: inclusive vocational guidance, student internships, school development, teacher professionalization

Inclusive vocational guidance as research subject and desideratum

Vocational training in Germany can resort to a theoretical basis labelled »integration«, which aims at offering people with special needs unrestricted access to and participation in vocational trainings and professional life (Enggruber and Ulrich 2016, 59; Biermann 2007, 9–10; Seyd et al. 2012, 23). Inclusive vocational guidance at school is a basis for such participation, but has, as yet, hardly been noted by research.

Although schools can assist the vocational orientation process only as facilitators and for a limited period of time (Famulla 2013, 18), they are highly relevant due to their importance in the students’ biographies (Knauf 2009, 229; Bergs and Niehaus 2016a, 1). Vocational guidance is tied to a complex network of requirements and needs, both institutionally and individually (Knauf 2009, 279). The educational staff in charge needs specific qualifications (ibid, 238). Empirical studies on inclusive vocational guidance, especially on the part of the schools as well as on the professionalization and qualification of those involved are a desideratum (Moser 2016, 668; Bergs and Niehaus 2016b, 296; Buchmann and Bylinski 2013, 185–192).

The research project »BEaGLE – vocational guidance as part of inclusive learning in secondary schools «1 examines how inclusive vocational guidance should be designed (Bienengräber et al. 2019). The aim of the project is to provide a targeted qualification matrix for teachers and other educational staff. In a specially devised mixed methods approach (Creswell et al. 2011), the first empirical access is qualitative in order to describe qualification requirements from within the educational practice. In a quantitative phase that is yet to come, these qualification requirements will be reviewed by means of a nationwide questionnaire survey. This will form the basis for the development of the qualification matrix.

The partial study presented here stems from the qualitative empirical phase of the project. It focuses on the organisation of work placements for students as an important aspect of inclusive vocational guidance at schools. This seems to set the biggest challenges regarding inclusive vocational guidance at school. Chapter 2 describes these challenges as they are key to choosing the work placement for students as focus of this partial study, which is presented in chapter 3. The presentation of the research design in chapter 4 highlights the methodical approach. The results (chapter 5) focus on organisational aspects of work placements in inclusive vocational guidance and form the basis for deducing the competences of teachers and other educational staff that can be seen as prerequisites for the success of this part of inclusive vocational guidance.

Challenges in inclusive vocational guidance at school

There are three main challenges: (1) deficits and differences in teacher training and the curricula of different study courses, (2) cooperations within, between and outside schools, especially regarding (3) the clarification of competences and responsibilities for vocational guidance.

Deficits and differences in teacher training and the curricula of different study courses

The »standards for teacher training« in educational science do not stipulate specific competences for the task of vocational guidance at school (Resolution of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany, dated 16. December 2004). Nevertheless, North Rhine-Westphalia, e. g., requires »basic competences for vocational guidance of students« for all teaching graduates and all school subjects (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung 2016, §10) as so-called »comprehensive competences« (ibid). Still, teachers lack specific knowledge and competences, which conflicts with the curricular requirements for vocational guidance – and explicitly also for the mandatory work placements for students – of secondary schools (Beinke 2013, 262–270). This is even more the case for inclusive vocational guidance. There is no concrete decree for this, merely the requirement that the school system should be developed inclusively (e. g. SchulG NRW, §2 Abs. 5). Consequently, the schools are required to develop concepts which consider the special educational needs of students.

Schools for children with special needs are in a different situation. Their educational programmes with different focal points of support2 generally aim at the same competences as those of general education schools and at the same learning objectives, at least a secondary modern school certificate (»Hauptschulabschluss«)3. Vocational guidance is a main topic related to guidance regarding practical life skills. There is even the demand to teach vocational orientation as a subject to prepare students early on for the vocational training system. Vocational and general education schools, however, do not provide for such a subject.

Therefore, in inclusive schools, many different curricula from secondary schools, schools for children with special needs, and vocational schools collide, as well as teachers with different subject, support, and learning field foci. This causes a significant need for qualification for the development of a single curriculum and related concepts.

Cooperations within, between and outside schools

The professionalization of teachers and other staff employed in inclusive vocational guidance focuses on the qualification for cooperations in their own schools, with other schools, and with external institutions. There is significant research on cooperations at schools in general, especially regarding different types and levels of cooperation (cf. overview Trumpa et al. 2016), but not regarding cooperations in inclusive vocational guidance at school. Such research is necessary, though, due to the growing complexity of cooperation structures because of the special educational needs.

Inclusive vocational guidance first requires cooperation within and between schools. Depending on the type of school, professionals from different areas come together, e. g., subject teachers, special education teachers, social workers, social education workers, and others. Special education teachers are essential for adding the special education perspective to the regular school system (Greiten et al. 2016, 154). This can also be assumed regarding inclusive vocational guidance.

External cooperations are a vital part of vocational guidance (Knauf 2009, 234–237); they connect vocational, economics, and special education teachers as well as in-company instructors (Weiser 2016, 20). Cooperations can also occur with institutions (Bergs and Niehaus 2016b) which are experienced in vocational guidance for people with or without special educational needs, such as vocational training and support centres, companies that take on trainees, employers’ associations or chambers. Vocational schools that have to deal with the same challenges in implementing inclusive education but have the necessary rooms and equipment, e. g., simulation offices, companies, and training workshops, etc. (in contrast to the regular equipment of general education schools) also lend themselves as cooperation partners.

Clarifying competences and responsibilities for vocational guidance

For the extensive task of vocational guidance, North Rhine-Westphalia, e. g., launched the study and vocational guidance, which is realized by coordinators (so-called »StuBos«). They are supposed to be the key contacts, internally as well as externally, and should also initiate the career or study choices at school and establish the relevant structures. This also needs to entail clarifying competences and responsibilities for the various partial tasks. Specifically, they are supposed to cooperate with the Career Counselling Offices of the Federal Agency of Employment and other external partners and organise the work placements and information sessions for the students (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung 2013, Chapter 1). Vocational guidance is seen as firmly established in most schools because of the activities of the »StuBos« (Euler and Severing 2015, 12). However, to fully achieve the desired effect, individual and institutional responsibilities for all partial tasks of the entire process need to be agreed and fixed.

To be able to fulfill their tasks, the StuBos receive further training according to the Ministry’s specifications; currently also for inclusive vocational guidance (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung 2013; Ministerium für Schule und Bildung 2016, §3). As there is a lack of reliable empirical findings, it is difficult to assess whether the quality of the offers is sufficient for providing effective vocational guidance. According to Loerwald (2011), the quality of, e. g., the work placement can be doubted as the specific knowledge and competences required go beyond the basic competences teachers have to demonstrate according to the regulations for teachers in North Rhine-Westphalia (»nordrhein-westfälische Lehramtszugangsverordnung«).

Against this background, we can not only assume multiple subjective qualification needs of the educational staff involved in the overall process, but also interpret the specific challenges the organization of work placements for students entails.

Work placements for students as core task of inclusive vocational guidance

Work placements for students bridge the gap between school and the world of work and training. There are many different types, such as alternative, long term, or vacation work placements (Berzog 2011, 7). They offer students the possibility to get to know a company hands-on. Thus, work placements provide, for a strictly limited period of time, what vocational guidance should provide in general: the transition from the school system into the system of vocational training and work.

Furthermore, work placements support the development of the student’s personality. Together with the knowledge acquired at school, the practical experience can serve as vocational information and orientation (Kremer and Gockel 2010, 3–4). Consequently, the work placement influences the personal development, motivation, specific vocational orientation, commitment, and knowledge transfer, especially from an inclusion perspective. Designing the work placement as a didactic unit, i. e., an extracurricular learning opportunity which requires targeted preparation and follow-up measures at school is a prerequisite for this. Far too often, however, the success of the work placement is challenged by coincidences. Choosing the company for the work placement because it is easy to reach by public transport and not for factual criteria is just one example (Kremer and Gockel 2010, 4). The didactic overall concept of the work placement, therefore, requires highly competent actors on the school side as this can certainly be described as a complex structural task. The success of this »highlight« of vocational guidance at school depends essentially on its quality (Berzog 2011, 3).

About the exploratory phase in the mixed-methods research design

Exploratory field access through group discussions

There is hardly any research in the area of inclusive vocational guidance at school. In order to identify relevant topics and key questions, an initial exploratory access to the field of practice in the shape of group discussions seemed appropriate (Kühn and Koschel 2018, 39). For this, people with experience in inclusive vocational guidance were brought together. It is assumed that participants bring experiences with related »knowledge and meaning structures«, and, thus, share a common area of experience, which enables them to ›understand each other as a matter of course‹ (Gurwitsch 1976, 178, in Przyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr 2014, 91). Knowledge plays a special part here, as the actors acquire it during their practical experience while it also serves as orientation. This basic understanding of a conjunctive space of experience cannot only be applied for people who know each other, but also for those who do not, as long as they interact in similar social situations as is the case in inclusive vocational guidance. To make the shared knowledge available in group discussions, the discussion should have its own momentum and not be chaired (Przyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr 2014, 92), so that participants may set their own agendas. Intensive discursive passages are particularly appropriate to analyse these common knowledge bases and collective orientations.

Through literature review and conversations with teachers from various school types, we first collected the occupational groups involved in the field of practice of inclusive vocational guidance and searched for relevant institutions in three cities of North Rhine-Westphalia. Based on this, acquisition of potential discussion participants began, by email or directly by telephone (Przyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr 2014, 59). We could recruit representatives from secondary schools in North Rhine-Westphalia (vocational schools for business and administration/technology/social work/special education, schools for children with special needs, comprehensive, and all levels of secondary schools), from regional federal agencies and Career Counselling Offices, chambers and various departments. Cross-regional representatives from teacher training centres and various associations agreed to join.

For the data collection, 18 group discussions with each five to six participants from different institutions involved in inclusive vocational guidance took place. In forming the groups, we aimed at maximum institutional heterogeneity in order to tap the full range of experience. Central questions as stimuli for the group discussions related to (1) requirements of inclusive vocational guidance, (2) descriptions of the competences they deem necessary for it, and (3) the importance of cooperations and networks.

The group discussions lasted between 80 and 90 minutes. They all ran autonomously and contained passages with dense descriptions and discursive parts. As the participants did not know one another, this can be seen as an indicator for shared experiences. In the communication, ›understanding each other as a matter of course‹ was obviously possible. Without any direct stimulus from the facilitators, one key topic with manifold knowledge bases crystallized in all group discussions: the work placement for students as key task of vocational guidance, especially in an inclusive context. Therefore, we chose the organisation of work placements for students and the competences required for this for the partial study presented in this paper.

Partial study on the organisation of work placements for students

The aim of the partial study presented here is to describe competences for teachers and educational staff deemed as prerequisites for the success of inclusive vocational guidance at school. There are two main research questions:

Who organises work placements for students in inclusive vocational guidance at schools and how?

Which are the core competences for organising work placements for students in inclusive vocational guidance according to the various actors?

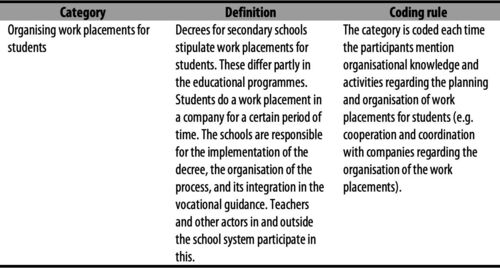

From the sample of 18 group discussions, six were picked which cover the widest possible range of represented institutions. To answer the research questions, the group discussions were assessed by means of a qualitative content analysis based on Mayring (2015). In line with the exploratory nature, the categories were formed inductively (Mayring 2015, 85f.; Kuckartz 2014, 72–78). According to the general procedure, the category system was concurrently validated in research workshops and the intersubjective traceability was observed for the pilot phase. The evaluation of the transcripts was done with MAXQDA 2018. Two coders each coded the transcripts independently and double-checked their results concurrently. The extract from the coding guidelines documents the coding process.

Extract from the coding guidelines

The analysis of the group discussions focused on deducing descriptions of competences for the organisation of work placements for students in inclusive vocational guidance at secondary schools.

Results of the qualitative content analyis4

Aspects of organising work placements as part of inclusive vocational guidance in the school system

During the analysis, three aspects transpired which are necessary to understand the importance of the work placements for students in inclusive vocational guidance: work placements for students as key point of reference for all actors, the decrees as legal background, and the responsibilities.

Work placement for students as key point of reference for inclusive vocational guidance

In all multi-professional group discussions, we identified the work placement for students as key point of reference for inclusive vocational guidance, next to topics such as how to shape the transition from lower secondary school to vocational training and the importance of networks and cooperations. The reason for the importance of the work placements and, thus, school development processes for all involved lies in the decrees as legal background, which was also mentioned in all group discussions as they provide the framework.

Decrees for organising work placements for students at school

Work placements for students are regulated by decrees for different school forms and educational programmes. Therefore, it is not surprising that all group discussions showed that work placements for students are seen as an implicit part of vocational guidance and are firmly integrated in the school system through more or less clearly devised concepts, schedules, and responsibilities. This implicitness is more pronounced in secondary schools than in vocational schools, where work placements are not integrated in all educational programmes. During the group discussions, teachers and social workers at vocational schools pointed out the special educational programmes to prepare for training or work (BfA1 17, EfA1 23, CfA2 68, BmN1 40).

Responsibilities

In all group discussions from the sample, teachers with responsibilities and assignments are identified as actors who organise work placements. This is the case for the organisation of the work placements on a conceptual as well as individual level, and also for the support of the students during the work placement.

Only in few schools, mostly vocational schools, this responsibility falls to the social workers (BmN1 40). Two extracts document their position in vocational schools. They can be responsible for all students under vocational guidance:

»and this is the actual problem for us, if you look at it from the other side, we only have the students for one year in training preparation, that means, I am head of the class together with the social worker who supports the students during the work placement, [sighs] but I am getting, have been getting to know them properly only now« (CfA2 68).

If the discussion is specifically about students with special educational needs, the issue for the vocational school is the wish for a specialised social education worker:

»that need to be (.) treated somehow, the students must be taken care of in the widest sense. (.) is a huge problem for us, as we (.) no one comes from (.) social education« (BfA1 17).

Obviously, one assumes further skills that one supposes social workers and social education workers have, but one lacks.

The »StuBo« teacher or coordinator assumes a role that is not only connected with their responsibility for the whole school but also with further education. Their area of responsibility widened regarding the necessary knowledge, the extension of the cooperations, and the scheduling:

»The organisation of KAoA demands the ›StuBo‹ coordinator’s full attention, so that (.) now the, the individual particularities of inclusive vocational orientation, that need to be considered, special appointments as, for example, the – not the regular job coach of the Agency of Employment is responsible for these children, but the rehabilitation counselling, these are extra appointments« (EfA2 22).

Responsibilities in the inclusive system change when special education teachers enter the system. No matter, whether they participate in a steering group for vocational guidance, they are declared as in charge of the group of students with special educational needs:

»Eventually, I was informed, as it is, informally, [Name], you do that, see, if they can go into the regular work placements or not« (AmA1 12).

The StuBos or other educational staff working in vocational guidance are still responsible then, but part of the responsibility is delegated to the special education teacher (for example AmA1 12) or claimed by them, as they feel responsible (e. g., CfA1 18).

The descriptions of the contexts of organising work placements give rise to questions about the competence profiles of teachers and educational staff working in inclusive vocational guidance. The data analysis provided three distinct areas of competence that were discussed by the participants: knowledge, action, and other skills. These will be described in the following.

Knowledge regarding inclusive vocational guidance

In the group discussions, knowledge about students and knowledge about organising work placements could be identified as key knowledge areas in inclusive vocational guidance.

Knowledge about students

Knowledge about students can be grouped along those with special educational needs, those with special needs, and those without the mentioned needs, for whom the data does not provide any further information regarding their learning disposition.

Some descriptions the participants gave relate generally to the group of students with special educational needs, where special requirements have to be considered regarding the preparation and realisation of work placements. It was generally expressed, that the workload, punctuality or mental problems can be fundamental problems (DfAk1 43; AmA1 12). Regarding students with the focal point of support mental development, the participating special education teachers clearly stated that these could not take part in »regular work placements« (AmA1 12) or that is particularly difficult for them (DfA2 95). There is a demand for other forms of organizing the work placements.

To what extent students with the focal point of support learning (AmA1 12) and emotional-social development (AmA1 12) can take part in regular work placements also depends on individual conditions. Both support areas are associated with the assumption that these students have little stamina and endurance, are hardly motivated or even disinterested (AmA1 12, CfA1 18). Regarding learning, it is explicitly stated that these students need something »different« (CfA1 18; AmA1 12), which is then explained: the form of the work placement, ideally a long-term placement, and also the way the companies deal with this student group: »caring […] with the patience of a saint« (DfA2 23).

Special physical needs as in the focal point of support seeing illustrate, how individually the work placements are organised. The extent of the disability and the desired company for the work placement must fit. A disability described as »half blind« (AmA2 12) does not require any specific conditions. Furthermore, the work placement option »office management« is pointed out for visually impaired people (EfA1 23), the fit is unproblematic. That changes when the impairment is stronger or the person is fully blind; jobs in the field of painting and decorating are not feasible then (AmA1 117).

Twice in the group discussions, students with autism are referred to. While their special need has hardly any impact on the choice of work placement, the integration support officers are being discussed (CfA1 18, EfA1 23).

Some parts of the group discussions require knowledge about students who are categorized in the analysis as students with special needs. These are students without special educational needs who – according to the teachers – still have special requirements which are relevant when choosing or supporting the work placement (DfAk1 43). The descriptions here include »difficult students«, »no motivation«, partly also »refugees« (BfA1 17; EfA1 23; AmA1 117; BfA2 19).

The third group refers to students without known needs who can usually do the work placements devised by the schools in the view of the participants. The participants mostly refer to that group as a contrast: there, everything works »regularly«, there, the regular responsibilities, such as the »job office« (AmA1 12) apply. The tenor in the group discussions is that the »ways« the students take in inclusive vocational guidance, or at least into the work placement, differ depending on whether and which needs they have.

Knowledge about organising work placements

The knowledge about organising work placements brought by the participants mostly refers to the schools’ own concepts, organisational structures and people involved. Participants from the institution »school«, such as subject teachers, special education teachers, and social workers put forth that their schools have a concept for vocational guidance. The descriptions of concepts for inclusive vocational guidance then mostly relate to students with special educational needs or other requirements. Concepts for inclusive vocational guidance are usually still being devised and often conceived as diffuse. No group discussion yields a description of a school’s own, complete concept.

Descriptions of the organisational structure show distinct differences between special education teachers and subject teachers. The former have experiences with vocational guidance in special schools and use these as a ›reflection foil‹ for the current situation at the schools they are sent to:

»And (.) we had, I was at a special school, and there we had a vocational support officer who basically managed it all. We actually had fixed networks, fixed (.) yes, fixed companies where we could find placements, well, I would say a list with 50, 60 companies, who basically were in the know, for years. And we always strengthened these networks and the vocational support officer or career counsellor from, from, from the emp, the employment agency then found placements for these students there« (AmA1 12).

Special education teachers as well as secondary modern school teachers with similar experiences (BfA2 19; DfA2 23; AfA2 45; CfN1 75; BfA 17), describe contacts with the employment agency, workshops for people with special needs or other institutions, the cooperation with vocational support officers, rehabilitaion counsellors, the integrational service, and most of all with those companies that also take students with special educational needs or other requirements for work placements, as resources. This goes hand in hand with knowledge about the preparatory and accompanying processes. Against this reflection base, special education teachers point out that such resources and experiences are not available within the system of general education and vocational schools, but need to be newly established.

With inclusive vocational guidance, new forms of work placement which go beyond regular work placements enter the system: day and long-term placements:

»Well, I have experience with inclusive vocational guidance inasmuch as I intensively accompanied the one-day work placement at the special school where I worked before. Our students had one fixed day at school [deep breathing] where they went into the companies, that went on for the whole year, for several years« (AfA2 14).

These forms offer possibilities to bring students into companies for one or several days a week, or even for several weeks or months to thus improve the transition into a vocational training. This form is possible in special schools due to the flexible organisation options in the higher grades, but is limited in regular schools because first, the relevant school development processes need to be initiated and the resources described need to be established.

»The most important thing was that we, the teaching staff always also thought of vocational preparation. We adapted things, we did early work and study guidance from grade 5 at my school, day work placements, individual work placements and such, but that only worked because we were relatively small teaching bodies [deep breathing], we knew the students« (DfA2 23).

In contrast to the special education teachers, the subject teachers of secondary schools comment more on responsibilities. Teachers for classes of refugees, the ›StuBos‹ and vocational orientation offices can be identified as superordinate competence or social workers/social education workers (CfA2 68).

Other knowledge areas, which cannot be discussed in detail here, refer to the programme »KAoA – Kein Abschluss ohne Anschluss«5, potentials analysis options also for students with special educational needs, details of schools’ own concepts for vocational guidance (BfA1 17; DfA1 19; DfA2 23; EfA2 22) and the support during the work placement (DfAk1 43).

Actions in inclusive vocational guidance

Within the data, the actions of individual teachers, which are often marked by the personal commitment for students with special educational needs or special requirements, are described in detail (DfA1 25, AfA2 45). These actions are reflected in finding a work placement and partly accompanying it: »companies that fit to the students are searched for« (BfA1 26), »must I maybe find another company« (AmA1 117) and teachers go »with them to the companies« (BfA2 19). One teacher states that personal »commitment« and a lot of »own initiative« are required to realise individual vocational guidance, »looking for a work placement is challenging« (EfA2 17).

Once more, the reflection foil special school presents itself: among the teaching staff, vocational preparation was always »thought of«. In a small system, in a small team, flexible, student-oriented actions were always possible, to the point of accompanying the students, even in the families (DfA2 23). One could »try out things« and »work differently« at special schools (AfA2 14).

In one passage, the lessons are discussed as part of the preparation for the work placement and it is argued that for certain periods of time it might make sense to teach exclusively in order to convey knowledge and attitudes and practice behaviour that help students with special educational needs acquire more self-confidence for the work placement and help them »keep up with others« (EfA2 22). According to this way of reasoning, periodical exclusion to build specific competences is sensible for inclusion.

In the following we will describe superordinate skills and competences of actors in inclusive vocational guidance which are connected with the areas of knowledge presented and partly also with the actions in the work placement field.

Superordinate skills and competences in inclusive vocational guidance

Generally, we should note that inclusive vocational guidance draws on the concept for general vocational guidance established at the respective school, broadens it or develops it further in parallel and, thus, separately. Descriptions of competences for inclusive vocational guidance can be deduced from the statements of the participants. These competences should be fulfilled to various degrees by the teachers, depending on their assigned or assumed responsibility. The descriptions of some competences mostly refer to the process of concept development and implementation as an innovation in school development due to the impementation of inclusive vocational guidance. This innovation process usually illustrates the context on which the arguments regarding competences are based in the group discussions.

One important competence without which the process of organising work placements in inclusive vocational guidance cannot be successful is knowledge building. Areas of knowledge have already been described. Based on the group discussions, we can state that knowledge about legal and curricular requirements has to be built through information acquisition, e. g., reading and exchanging information with other people and professions. The latter is important as the topic area is complex and includes other people’s know-how. Being able to verbalise know-how, e. g., about the processes of organising work placements at the respective schools and also at special schools should be considered particularly for an exchange that aims at knowledge building. The competence to build knowledge about special educational needs as well as about the curricula of different educational programmes is pivotal. This is a requirement for all educational staff, also special education teachers if they lack knowledge about specific needs (AmA1 12).

Another area of competence relates to direct educational work with students with special educational needs and other requirements. One example is to motivate disinterested students »to commit themselves« (CfA1 18) and to develop an individual »vocational perspective after school« with them (BmN1 40).

This competence is connected to another one, namely the matching of students and companies (DfAk1 43, BfA2 19, DfA2 23, CfN1 75), expressed in phrases such as »pilot them into a work placement« (BfA1 17). This competence stands out in the group discussions as it relates to finding a work placement that fits to the individual prerequisites and requirements. As already described in the focal point of support seeing, this fit is important for every work placement:

»Well, when someone is completely blind, it is different, of course, I deal differently, I need to maybe find another company. It can’t be, (2) I don’t know, maybe he can, but with a painter it is, of course, difficult« (A1 117).

One major area of competence is cooperating on several systemic levels, which, first of all, requires social and communicative competences. Within a school, cooperations take place between teachers and other educational staff, especially with class teachers (CfN1 75) at class level. Additionally, there are cooperations with actors from the school in work groups and the ›StuBos‹ (AmA1 12). The third cooperation level refers to institutions outside one’s own school, e. g., the employment agency (CfN1 75, DfA2 23), the advanced vocational school (CfN1 75), and the work placement companies.

Furthermore, competences in concept development and management are needed to organise work placements. This entails constructing organisational structures at various school levels and developing a curriculum for work placements within inclusive vocational guidance which also considers specific educational needs. Within this process, special education teachers perceive themselves as a key function: they describe their role i. a. as the transformation of knowledge about work placement organisation at special schools to general education and vocational schools. This transformation is especially important as it entails developing concepts for the organisation of work placements for students with special educational needs in larger systems as, e. g., special schools (AmA1 12, AfA2 14, BfA2 19, DfA2 23). This poses a challenge for both, the special education teachers and the cooperating teachers; statements of special education teachers express this transformation issue regarding concept development and management:

»Nowadays we must get along in unmanageably vast systems, where we (.) I don’t know, where are we, in, in [sighs] you can’t measure it anymore, that’s the percentage we are at with our students in=the large comprehensive school, we are utterly meaningless. And everything we have experienced, the colleagues haven’t made these experiences (.) in their socialisation (.) How does one convey this now?« (DfA2 23).

The topic here is not knowledge transfer, or, as one participant demands, »knowledge management« regarding responsibilities and knowledge: »the regular for the mass of students« versus »specifics« for inclusive students (EfA2 17), but the competence of sensitization connected with it; to »sensitize« the colleagues to the requirements of students with special educational needs that these (author’s note: the quote refers to the special educational need learning) »need something very different from the regular comprehensive students who can look forward to at least achieving the secondary modern school certificate« (CfA1 18).

Modes of reasoning regarding student groups, responsibilities, and ways into work placement

In the discussions, certain modes of reasoning of the participants can be detected regarding a practiced triadic connection between classification into a student group, responsibilities of the actors, and the way into work placement. One mode of reasoning refers to contextualising inclusive vocational guidance, i. e., orienting it to students with special educational needs. Another mode of reasoning presents itself in the differentiation of student groups for whom inclusive vocational guidance is conceptualised differently: students with special needs, with special educational needs, and without special needs. A third mode of reasoning relates to these student groups as reference for

the choice of business area and the precise profession the work placement should be done in,

the choice of a specific company/institution,

the way into the work placement (fitting company – intern),

subject-specific conditions of the interns for doing the work placement in the chosen company (e. g., motivation).

The fourth mode of reasoning refers to differentiating the actors, their addressing and commitment to the organisation of work placements: the ›StuBos‹ and other teachers in charge of this task, e. g., class teachers, social workers/social education workers (if they are incolved in coordination), and particularly special education teachers if they are involved.

Actor’s modes of action within the framework of conditions of the school system

After analysing how the actors conceptually develop the organisation of work placements in inclusive vocational guidance, we can describe modes of action of the actors within the framework of conditions in their individual school systems. These partly result from the formally given or assigned responsibilities of the various professions: In the first mode, special education teachers claim inclusive vocational guidance as their field of action, with or without informing the ›StuBos‹. In the second mode, the ›StuBos‹ habitually delegate and expect feedback. They or the school administrators decide the responsibilities of special education teachers or social workers/social education workers for students with special educational needs. They want to be kept informed, but do not act group-oriented for students with special educational needs or subject-oriented in individual cases. In the third mode, ›StuBos‹ and special education teachers (and, in case, social education workers) cooperate regarding students with special educational needs and other requirements.

The first two modes of action lead to uncoupling inclusive vocational guidance of the vocational guidance established at schools in three ways and, thus, to excluding work placements, as one can see in the organisation of work placements: separating the students with special educational needs by giving them a ›different‹ preparation and choosing companies deemed particularly suited. Furthermore, the first two modes lead to dividing the tasks of the teaching staff into responsibilities for students with and without special educational needs. The third mode of action also focuses the cooperation of ›StuBos‹ and special education teachers/special education workers on students with special educational needs, but also on students without special educational needs whom teachers still assign certain requirements. For the latter, more individualised work placements are considered.

Summary and discussion of the results

The partial study presented here investigated who organises work placements for students in inclusive vocational guidance and how, and what competence profiles can be deduced from the actors’ points of view. For this, we evaluated group discussions with multi-professional experts. Due to the sampling, the results outrange the group discussions though being bound to the legal prerequisites in North Rhine-Westphalia. The reason for the methodic approach of group discussions with only few stimuli lies in the exploratory approach and aims to enable a wide range of topics: assuming that the participants could put forth their concerns from their individual systemic backgrounds, the discussions yielded requirements and respective competence profiles stemming from different institutional perspectives. The results presented here for the competence profiles are based on individual assessments of the participants or on deductions the authors verbalized from implicitly documented knowledge. The assumption that some competence descriptions might be valid only for specific professions is currently reviewed in a more in-depth evaluation. In the following, we will discuss selected results.

The definition of inclusive vocational guidance remains diffuse with the educational staff but is linked to students with special educational needs. This leads to a narrow perception of the term inclusion from the participants as is often the case in the current discussion. This, in turn, raises the question about the difference between inclusion and integration. The participants, however, widened their focus to also include students with special requirements without a diagnosis of special educational needs.

When considering inclusive vocational guidance, the participants thought first and foremost of work placements for students, their initiation and realisation, and, secondly, also the follow-up and reflection. Tuition is hardly a topic in connection with inclusive vocational guidance. This is confusing, as decrees usually stipulate such a connection to class tuition. The lack of discussion about class situations might be due to the multi-institutional group composition and could be different in group discussions with teachers only. This question should be looked at in the future.

nIt should be investigated to what extent this may lead to excluding practices in the communication and reasoning and further in the actions of the actors; on student, teacher, and company level; and how these are reflected in the concept for inclusive vocational guidance.

Perceiving competences as success factors for the analysis, the participants’ thoughts in the group discussions yield two points of reference: which type of work placement is suitable for which student at what point in their school career and how the work placements are initiated and supported within and outside school. What can be noted in the analysis of the group discussions is that these questions are even more to the fore when thinking about inclusive vocational guidance than is usual in discussions at special schools or secondary modern schools with »BUS«6 classes and concepts for long-term work placements. In inclusive classes characterised by the fact that they enable joint learning of students with and without special educational needs, the development of the school system towards inclusive vocational guidance can be perceived also from the answers to these questions.

The results highlight the connection between the understanding of inclusion at schools and its effects on tuition and inclusive vocational guidance. Can processes of realising inclusion in class also be found in realising vocational guidance? Are special education teachers, e. g., assigned responsibility for the inclusive vocational guidance, maybe even sole responsibility for students with special educational needs? In class, other practices could be applied: there, the subject teachers are in a dominant position and the special education teachers support them or they have separate learning groups for students with special educational needs.

Addressing the actors and describing their activities in organising work placements is initially ruled by regulatory requirements but within this scope, negotiation processes between the people and institutions involved occur. However, there is not enough research on these processes or on the changing role of the ›StuBos‹. Again, the challenge seems to be that it has to be clarified within the systems which actor is responsible for what.

Several times, the results show a transformation problem: transforming knowledge, practices and structures from special schools to schools becoming inclusive does not or hardly work. Knowledge, practices and structures that were once available are lost.

Future research on inclusive vocational guidance should discuss the identification of fields of action, roles, and cooperations of actors, and, first and foremost, identify knowledge references that result subject-specifically from the requirements of students with special educational needs and point out consequences for inclusive vocational guidance.

Annotations

- [1]

- Funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Funding reference numbers: 01NV1723A (partial project University of Duisburg-Essen) and 01NV1723B (partial project University of Wuppertal).

- [2]

- North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) mentions, e. g., »learning«, »language«, »emotional and social development«, »hearing and communication«, »seeing«, »mental development«, and »physical and movement development« as focal points for support (vgl. Schulgesetz NRW 2014, additionally, the Ministry for Education North Rhine-Westphalia NRW points to autism spectrum disorders.

- [3]

- The exception are students with the focal points of support »learning« and »mental development«, who pursue different degrees within the framework of target-specific learning (Schulgesetz NRW 2014, §12 [4]; §19 [7]).

- [4]

- In the results section, we use abbreviations for references from the group discussions, which cannot be explained in more detail here for lack of space, e. g. BfA1 17: Name, gender, group, and paragraph.

- [5]

- The abbreviation »KAoA« stands for North Rhine-Westphalia’s programme for vocational guidance called »Kein Abschluss ohne Anschluss«, which establishes a common system for vocational and study guidance for North Rhine-Westphalia.

- [6]

- The abbreviation »BUS« stands for »Betrieb und Schule«. This is a project funded by the Federal State North Rhine-Westphalia for underprivileged adolescents to support them in choosing a profession and a work place and integrating them into the working world. It is aimed at students in their tenth year of schooling without a chance of obtaining a regular school certificate.

Bibliography

Beinke, Lothar. 2013. »Das Betriebspraktikum als Instrument der Berufsorientierung.« In: Berufsorientierung: ein Lehr- und Arbeitsbuch, herausgegeben von Timm Brüggemann und Silvia Rahn, 261–271. Münster: Waxmann.

Bergs, Lena und Mathilde Niehaus. 2016a. »Bedingungsfaktoren der Berufswahl bei Jugendlichen mit einer Behinderung. Erste Ergebnisse auf Basis einer qualitativen Befragung.« bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik online 30: 1–14.

Bergs, Lena und Mathilde Niehaus. 2016b. »Berufliche Bildung.« In Handbuch Inklusion und Sonderpädagogik, herausgegeben von Ingeborg Hedderich, Gottfried Biewer, Judith Hollenweger und Reinhard Markowetz, 293–297. Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

Berzog, Thomas. 2011. »Das Betriebspraktikum als Instrument schulischer Berufsorientierung.« bwp@ Spezial 5: 1–12.

Bienengräber, Thomas, Thomas Retzmann, Silvia Greiten und Lütfiye Turhan. 2019. Berufsorientierung im gemeinsamen Lernen der Sekundarstufen – Entwicklung eines Qualifikationstableaus für pädagogische Fachkräfte. In Lehren und Lernen im Spannungsfeld von Normalität und Diversität, herausgegeben von E. von Stechow, K. Müller, M. Esefeld, B. Klocke und P. Hackstein. Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Biermann, Horst. 2008. Pädagogik der beruflichen Rehabilitation. 1. Aufl.: Heil- und Sonderpädagogik. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Buchmann, Ulrike und Ursula Bylinski. 2013. »Ausbildung und Professionalisierung von Fachkräften für eine inklusive Berufsbildung.« In Inklusive Bildung professionell gestalten. Situationsanalyse und Handlungsempfehlungen, herausgegeben von Hans Döbert und Horst Weishaupt, 147–202. Münster: Waxmann.

Creswell, John W. und Plano Clark, Vicki L. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (2. Aufl.), Los Angeles: Sage.

Enggruber, Ruth und Joachim Gerd Ulrich. 2016. »Was bedeutet ›inklusive Berufsausbildung‹? Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Berufsbildungsfachleuten.« In Inklusion in der Berufsbildung: Befunde – Konzepte – Diskussionen, herausgegeben von Andrea Zoyke und Kirsten Vollmann. Bielefeld: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung.

Euler, Dieter und Eckart Severing. 2015. Inklusion in der beruflichen Bildung. Chance Ausbildung, herausgegeben von Bertelsmann-Stiftung. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann-Stiftung.

Famulla, Gerd-E. 2013. »Erfahrungen aus dem Programm Schule-Wirtschaft/Arbeitsleben.« In Arbeitsweltorientierung und Schule – Eine Querschnittsaufgabe für alle Klassenstufen und Schulformen, herausgegeben von Gewerkschaft Erziehung und Wissenschaft Hauptvorstand, 11–41. Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Greiten, Silvia, Eva Kristina Franz und Ina Biederbeck. 2016. »Wodurch konturiert sich die sonderpädagogische Perspektive und wie gelangt sie in den inklusiven Unterricht an Regelschulen? Befunde aus Gruppendiskussionen zu Erfahrungen aus der Netzwerkarbeit von Sonderpädagoginnen, Sonderpädagogen und Regelschullehrkräften.« In Kooperation im Kontext schulischer Heterogenität, herausgegeben von Annelies Kreis, Jeannette Wick und Carmen Kosorok Labhart, 143–158. Münster: Waxmann.

Gurwitsch, Aron. 1976. Die mitmenschlichen Begegnungen in der Milieuwelt. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Knauf, Helen. 2009. »Schule und ihre Angebote zu Berufsorientierung und Lebensplanung – die Perspektive der Lehrer und der Schüler.« In Abitur und was dann? Berufsorientierung und Lebensplanung junger Frauen und Männer und der Einfluss von Schule und Eltern, herausgegeben von Mechtild Oechsle, Helen Knauf, Christiane Maschetzke und Elke Rosowski, 229–282. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kremer, Hans-Hugo, und Christof Gockel. 2010 »Schülerbetriebspraktikum im Übergangssystem – Relevanz, Potenziale und Gestaltungsanforderungen.« BWP@ 17: 1–28.

Kuckartz, Udo. 2014. Mixed Methods: Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Kühn, Thomas und Kay-Volker Koschel. 2018. Gruppendiskussionen: Ein Praxis-Handbuch 2. Aufl., Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kultusministerkonferenz. 2007. Handreichung für die Erarbeitung von Rahmenlehrplänen der Kultusministerkonferenz für den berufsbezogenen Unterricht in der Berufsschule und ihre Abstimmung mit Ausbildungsordnungen des Bundes für anerkannte Ausbildungsberufe. Bonn: Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz, Referat Berufliche Bildung und Weiterbildung.

Loerwald, Dirk. 2011. »Das Schülerbetriebspraktikum – Betriebe als außerschulische Lernorte.« In Methodentraining für den Ökonomieunterricht 2, herausgegeben von Thomas Retzmann, 125–140. Schwalbach/Ts: Wochenschau-Verlag.

Mayring, Philipp. 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 12. Aufl. Basel: Beltz

Ministerium für Schule und Bildung. 2013. Berufs- und Studienorientierung. Runderlass des Ministeriums für Schule und Weiterbildung v. 21.10.2010 i. d. Fassung vom 01.04.2013. Herausgegeben vom Ministerium für Schule und Bildung. Düsseldorf.

Ministerium für Schule und Bildung. 2016. Verordnung über den Zugang zum nordrhein-westfälischen Vorbereitungsdienst für Lehrämter an Schulen und Voraussetzungen bundesweiter Mobilität, herausgegeben vom Ministerium für Schule und Bildung. Düsseldorf.

Moser, Vera. 2016. »Professionsforschung.« In Handbuch Inklusion und Sonderpädagogik, herausgegeben von Ingeborg Hedderich, Gottfried Biewer, Judith Hollenweger und Reinhard Markowetz, 277–287. Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

Przyborski, Aglaja/Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika (2014). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Ein Arbeitsbuch. 4. Aufl. München: Oldenbourg.

Seyd, Wolfgang, Willi Brand, Angela Kindervater, Jasmin Saidie und Burkhard Vollmers. 2012. Das Reha-Modell der deutschen Berufsförderungswerke – Sammlung von Dokumenten. Universität Hamburg.

Trumpa, Silke, Eva-Kristina Franz und Silvia Greiten. 2016. Forschungsbefunde zur Kooperation von Lehrkräften: Ein narratives Review. Die Deutsche Schule 108(1): 80–92.

Weiser, Manfred. 2016. »Professionalisierung durch die Kooperation von Berufs- und Sonderpädagogik – Erfahrungen und Anregungen.« In Inklusion als Chance und Gewinn für eine differenzierte Berufsbildung, herausgegeben von Josef Rützel und Ursula Bylinski, 199–211. Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Authors

Thomas Bienengräber, Prof. Dr. rer. pol. habil.; Chair of Business Education and Business Didactics; Project Manager BEaGLE, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg Campus; Fiel9ds of Research: Inclusive vocational guidance, curriculum development, moral development, situation research

Contact: thomas.bienengraeber@uni-due.de

Silvia Greiten, PD Dr. phil.; Research Assistant at the School of Education of the University of Wuppertal; Project Manager BEaGLE, University of Wuppertal; Fields of Research: School and teaching development in the context of heterogeneity, individual promotion, giftedness, inclusion, teacher professionalisation

Contact: greiten@uni-wuppertal.de

Thomas Retzmann, Prof. Dr. rer. pol. habil.; Chair of Business and Economics Education; Project Manager BEaGLE, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen Campus, Faculty of Business Administration and Economics; Fields of Research: Inclusive vocational guidance, Human capital development in the dual system of vocational training; economic education and moral education; vocational training and moral education; Entrepreneurship Education

Contact: thomas.retzmann@uni-due.de

Marie Schröder, M. A.; Research assistant on the BMBF-Project BEaGLE, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg Campus; Fields of Research: Inclusive vocational guidance

Contact: marie.schroeder@uni-due.de

Lütfiye Turhan, M. Sc.; Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Faculty of Economics and Business

Contakt: turhan@econ.uni-frankfurt.de